The Disseminary

What Theological Educators Need to Learn from Napster

A. K. M. Adam

Seabury-Western Theological Seminary

University of Glasgow

Oriel College, St Stephen’s House, University of Oxford

One of the pervasive phenomena of our digital moment has been the daily deluge of prophecies that assure us about what the future holds for cybercognoscenti.

The rate at which these predictions go unfulfilled has done nothing to diminish the sober-sided gawping with which news anchors and talk-show pundits greet the next round of predictions.

As David Weinberger comments, “[At this point, projections based on the present are worse than useless. And that, of course, is exactly how matters stand at the turn of the millennium when it comes to technology.] We’ve never experienced a period of such rapid change–especially when it comes to the Web. Making predictions in this kind of environment isn’t just foolhardy; it can be a kind of denial. ‘Tomorrow will be much like today’–yeah, you wish!” (“Predictions,” All Things Considered, August 22, 2000).

Educators have, in general, responded to the prognosticators–perhaps to some extent because changes in media require the kinds of budgetary decisions that can’t be made by teachers, but only by administrators; perhaps because the prognosticators get so much attention that even canny teachers fall for the hype. As a result, education’s flirtation with technology has typically involved spasmodic convulsions of expenditure and consequent disappointing results.

But Weinberger is right: we oughtn’t be counting on prognosticators to guide our expenditures or our pedagogical strategies. Circumstances are changing far too quickly to justify our investing in answers whose value will have evaporated by the time we have changed over our syllabi to the new standard technological gadgetry. Most faculty don’t have the time to waste by re inventing their teaching strategies with every wave of change.

The Disseminary: Planning for Change

The classic response to change involves desperate fears about control. How will we control who reads the Bible? How will we control where people travel? How will we control who can interpret the Dead Sea Scrolls? How will we control people’s acquisition of recorded music?

And the answer to these fears requires not a greater, stronger, firmer grip on controls, but requires us to learn from the change a new way of thinking about communication, about transportation, about interpretation, about digital information.

For instance, some academic administrators responded to the first wave of mainstream technological change entailed hiding from the Web, lest someone do something illegal or doctrinally incorrect in their webspace.

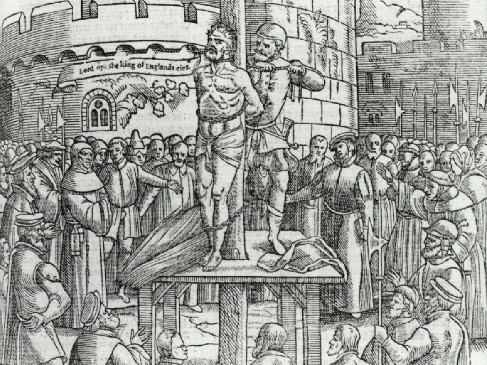

The impulse to tighten controls, to crack down, to prevent risk is just the response that the world of accelerating change will defeat, every time—as theological authorities and record companies ought to have figured out by now.

“If we burn a few more Lollards, maybe it’ll provide a disincentive for those rascally translators!”

Even if the recording-industry oligopolists successfully drive Napster underground, that’s all they will have done. There are today various ways to exchange files online different from that the Napster protocols Shawn Fanning devised a couple of years ago; by the time the recorded music industry stifles the next method of peer-to-peer file sharing, the ways of sharing music online will have multiplied even further.

While the record companies (and many musicians) shout “Piracy!” it’s worth stepping back for a moment and remember that the industry of recording particular performances and selling the recordings developed from a distinct set of technologies, a set of technologies which themselves transformed the economic processes through which musicians made their livings. (More to the point, they didn’t transform the ways most musicians make their living; they transformed the fortunes of a select few, improved the lot of a moderate number of intermediate-level musicians, and simply seduced and deceived a tremendous number of musicians who still make their livings just by waiting on tables or working in graphic arts houses, or who don’t make a living at all.)

“The history of the record industry is an aspect of the general history of the electrical goods industry, and has to be related to the development of radio, the cinema, and television. The new media had a profound effect on the social and economic organization of entertainment so that, for example, the rise of record companies meant the decline of the music publishing and piano making empires, shifting roles for concert hall owners and live-music promoters.”

— Simon Frith, “The Industrialization of Popular Music,” in Popular Music and Communication, James Lull, ed., (NY: Sage) 1992, p. 51.

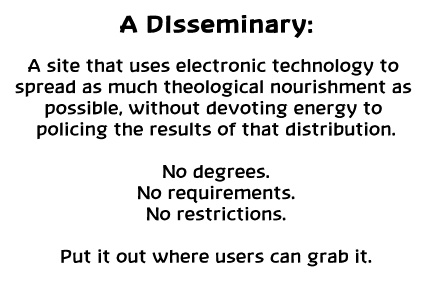

The Disseminary:

To An Unknown Medium

But the technology is changing again, and as interested parties fulminate against “piracy,” they no more discern the signs of the times than did the nineteenth-century impresarios who feared that the Edison cylinders meant that no one would ever attend live music concerts again. If we cling to models from an obsolescent social structure, our desperation portends only inevitable catastrophic failure. If we risk ventures that derive their coherence from the plate tectonics of contemporary information flow, and if we gauge our plans by the ways that change seems to be happening, and if we don’t pre-fossilize our plan with over-investment, we have at least a chance of taking part in a productive change in theological pedagogy.

The times are changing, and the model of intellectual property that derives from circumstances where only a few people had available the capital to underwrite the mass reproduction of information–that model of intellectual property no longer functions. Interested parties may keep it alive in a declining state of vitality, but the circumstances that supported the model no longer obtain. It’s over.

Theological educators? We enter the picture less as holders of intellectual property–though that’s a relevant consideration from which we need to wean ourselves–than as stewards of the mysteries, called to make known the gospel, with an eye open to where we should stand on Mars Hill and how much it costs. Some of us will reverently watch the death throes of nineteenth-century copyright law, chipping in to pay for life-support machines; others will concentrate on learning to imagine a different world of information sharing.

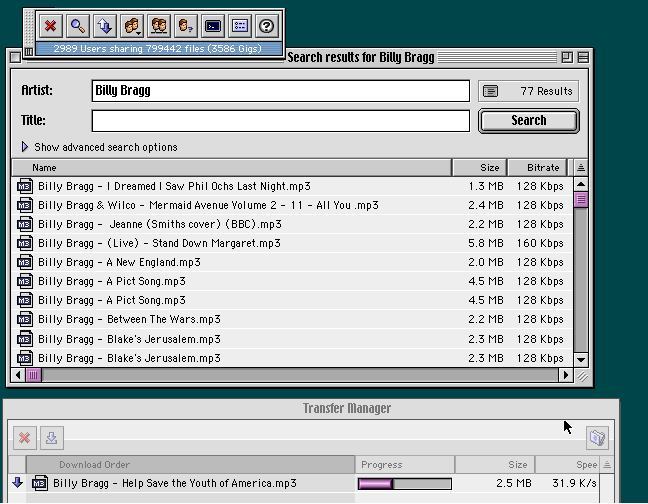

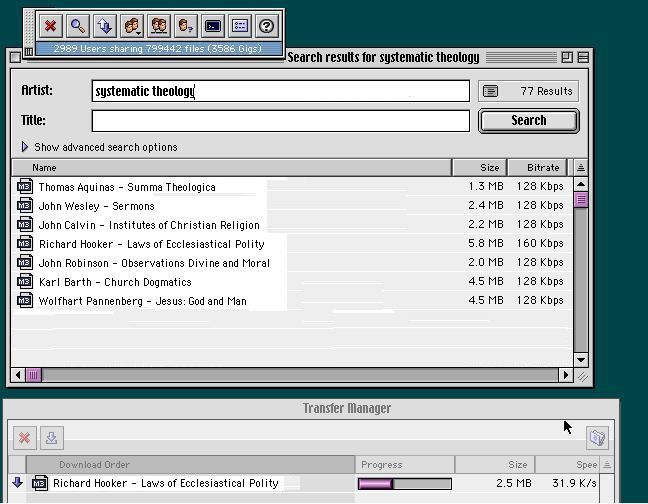

We can usefully take Napster as a model for that new world of information sharing–a plausible move, granted that it is arguably the most successful internet application ever released. Napster had tens of millions of users within months of its first appearance online, and has instigated fundamental changes whose outcome still isn’t clear. What does the staggering éclat of Napster have for theological educators?

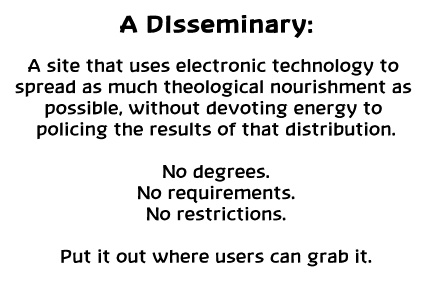

It suggests the possibility of a Disseminary, a common effort to put as much theological sustenance at the disposal of as many people as possible. It suggests that a Disseminary can serve the mission of theological education by raising the tide of theological literacy among its students and among interested bellievers (and non-believers). A Disseminary sets out as rich a banquet of theological wisdom as it can manage to offer, without trying to set standards for who consumes it, how well, when, how often, or… anything.

The institutional agility of a Disseminary derives from learning a few simple lessons from Napster. For instance, Lesson One–

The Disseminary:

Lesson One

1. It’s not the interface.

Have you used Napster? It’s as bare-bones a user experience as ‘most anything, and users would still be lining up to get hold of it even if it were command-line based. Shawn Fanning has bemoaned the rapid success and almost equally rapid legal miasmas Napster encountered, because he still isn’t done with the interface. According to Fanning, Napster is really at about the beta level of the product he’d want to have constructed.

The lesson for theological educators: Pictures, Flash animations, frames, MIDI music playing in the background, Javascript scrolling message space, all may enchant the Board of Trustees–but they all use up bandwidth for something that’s beside the point. If you offer people something they want to find, they will come.

You don’t need to reason from Napster; if you prefer to get this message from consultants, ask any of the “useability” experts (Jakob Nielsen, Vincent Flanders, David Weinberger, et al.).

Content is king. [Ed. I would seriously qualify this now, but in context it was apposite.]

All this is the more urgent and true for those of us who have been entrusted with a message, not a design. I love design, I used to work in design, but design has to come second to content.

The Disseminary:

Lesson Two

2. Free. Free. Free.

As a corollary of the marginal significance to the interface and of the imminent demise of copyright, the second lesson of Napster is “Free.” Give it away. If you need to bribe your faculty, staff, and students to produce noteworthy content to give away, do it. We’re cheap. I write a couple of articles a year for which I’m paid nothing. The published edition of my most weighty scholarly research project has earned me zero dollars.

The first time a denominational periodical sent me a check for a book review, I almost sent it back, thinking it had to be a mistake. For a hundred dollars here, fifty dollars there, a little course relief, a little work-study support, you will be able to extract vast amounts of content from most faculty. If you want to pinch pennies, you can make computer upgrades contingent on your faculty producing content. “Oh, you want a faster processor? Show us what you use it for….”

Of course, the catch here concerns whether you have faculty who can produce content that you’re proud to offer the world, that won’t tarnish your reputation more than burnish it. No one will turn the music industry upside down to get MP3s by Carsickness or the Cardboards (I liked them; I used to work with them; my point, however, is that the recording industry isn’t in an uproar to protect their performance rights). The industry cares when you can get all the tracks from Bruce Springsteen’s Live in New York City CDs from Napster before you can buy them at all, and when on Napster the recordings are free whereas you would pay $24.97 for them at Sam Goody. But the quality of the content you provide is between you and your contributors; that’s your problem.

The Disseminary:

Lesson Three

3. No one gets degrees or certificates from Napster or its users, and no one would care if they did. The music is its own reward.

You don’t have to apply to be a Napster user, nor do you get a certificate if you upload or download a lot. You spend time with Napster in order to be part of a music-sharing community.

In other words, theological educators, make your webspace a site for sharing theological information, and you will attract the attention and allegiance of users who want such sustenance. Don’t just think of the Web as a medium for a really extended extension program. You can, of course, use the Web to help organize and operate an existing extension program, in ways similar to the ways you could use photocopiers, cars, and so on. But the Napster model suggests that if theological educators see the internet only as yet another cash cow for administrative milking– “Now we can add students who need never darken our doors!”–they will tend to squander large amounts of capital on projects that fail , indeed, that defeat themselves. Does anyone remember giant black-and-white TVs on rolling gantries that were supposed to bring televised education to elementary schools? Theological educators don’t stand to make money by sucking it out of web users, any more than record companies will convert the Napster community to for-pay models of music distribution.

In webspace as in Scripture, “It is more blessed to give than to receive.” The degree-granting model or the certification model puts the server in the position of deciding who gets what, who’s gotten enough, who’s done enough–and we have insufficient data to assume that users will support such a model. Instead, give and give more. Differentiate the main use of theological webspace–disseminating the information–from possible secondary or tertiary uses (to enhance distance learning). If you make concessions to profit at the outset, the impulse to suck cash out of users will quickly eclipse better-supported (and theologically sounder) functions of your web presence.

In a fallen world, people will not en masse forego the appeal of certification and degrees. Make ’em come to you for the piece of paper. As for information, give it away.

The Disseminary:

Lesson Four

4. Users who have downloaded large amounts of music tend to be better acquainted with more music (duh!).

I now know a lot more about bands of whom I hadn’t even heard when I first encountered Napster. And I’ve bought CDs I wouldn’t have bought because I liked what I heard on Napster. If I were about to begin a three-year program of study on contemporary music, I’d be better informed than I would have been before Napster.

Lesson for theological educators: At a moment when seminarians arrive for their first classes knowing less and less about the traditions from which they ostensibly arrive, and for whose ministry they ostensibly are preparing, why not put energy into helping students learn more before they unpack on campus? If we devote our efforts to putting useable content into our webspace, we can reasonably expect that some incoming students will at least have bumped into the content we offer. Moreover, this will have the advantage of being the information we want them to have, configured to suit our curriculum and our pedagogical-theological interests–a big improvement over the miscellaneous introductory text whose precepts we may need to uninculcate after students arrive.

Moreover, that information will be sitting out there for people who may not even think they’d be interested in theological education, but who might become so if we offer readily-available enticements.

Moreover, the students who do come to us will have been conversing with fellow congregants who may themselves have been reading the Garrett, or Seabury, or Your-Institution’s-Name-Here website’s introductory material.

Moreover, the clergy out in the field may find in our web offerings helpful refreshers so that they don’t all turn into Sabellians the moment they graduate.

The more theological sustenance our students (and others) can explore in our webspace, the more theologically-literate they are likely to be.

The Disseminary:

Lesson Five

5. Users who are enthusiastic about music they download will buy the CD and will especially go to the concert.

I’m an old geezer, so my concert-going days are highly attenuated. I think Elvis Presley isn’t on the road as much as he used to be. But my sons, who still have eardrums and can stand up for hours on end (when they want to) are aching to get to a venue where they can watch their favorite performers, even though the admission prices now more closely resemble the cost of an emergency room visit than the spare change that I was charged in my youth.

Lesson for theological educators: Users who go to a Disseminary and there find interesting information, impressive scholars thinking in public, inspirational counsel, will not say to themselves, “Wow, I now know everything I need to know about theology.” And they’ll want to come to the people whose net persona so impressed them in the first place. And when they come they’ll be better prepared. Why not use the positive teaching capacities of your faculty to draw students to your seminary for the work that can only be done on-site?

The Disseminary: Give It Away

At what cost? Relatively little investment; most of the investment would come from faculty productivity, which is cheap–administrations get most of our additional capacity for free, after all–and renewable (especially if we see ourselves getting positive attention).

If theological educators will acknowledge technological change with a view toward the particular characteristics of cybermedia (and users of cybermedia), if they will allow themselves to think beyond the constraints of “the way we’ve always thought about media,” they can benefit from the lessons that Napster teaches.

Relinquish the need to control pedagogy.

Invite the world to learn what you want to teach it.

Welcome to campus those inquirers and students who want to learn more.

Give away everything that’ll go, and you can find out if what you’re offering is worth even a moment’s download. Give it away, and you can begin the task of theological education for a world of people who might not have thought to come to your physical campus before.

Give it away, because the things theological educators do best won’t ever be replaced by virtual instruction. So if we give away everything that’ll go over the web, we’ll be that much more free to concentrate on what we do best.

A. K. M. Adam

{at that time}

Associate Prof. of New Testament

Seabury-Western Theological Seminary

Evanston, Illinois

{now}

Tutor in New Testament

St Stephen’s House

University of Oxford

Many thanks to the Wayback Machine, through which I assembled this page form the following links:

http://web.archive.org/web/20060718192058/http://www.seabury.edu/faculty/akma/Dissem1.html

http://web.archive.org/web/20060718192058/http://www.seabury.edu/faculty/akma/Dissem2.html

http://web.archive.org/web/20060718192058/http://www.seabury.edu/faculty/akma/Dissem3.html

http://web.archive.org/web/20060718192058/http://www.seabury.edu/faculty/akma/Dissem4.html

http://web.archive.org/web/20060718192058/http://www.seabury.edu/faculty/akma/Dissem5.html

http://web.archive.org/web/20060718192058/http://www.seabury.edu/faculty/akma/Dissem6.html

http://web.archive.org/web/20060718192058/http://www.seabury.edu/faculty/akma/Dissem7.html

http://web.archive.org/web/20060718192058/http://www.seabury.edu/faculty/akma/Dissem8.html

http://web.archive.org/web/20060718065921/http://www.seabury.edu/faculty/akma/Dissem9.html

1 thought on “The Original Disseminary”