I’m always a bit slow on the uptake, and especially as Margaret and I have been particularly distracted during the past ten days or so; though I saw my friends and students and all posting comments about their sermons for Trinity Sunday, I didn’t connect the dots that the “26 May” on the rota that said I was on duty to preach also meant that I too would be expected to have something to say about that holy mystery.

I had preached recently — a couple of weeks ago, at St Aidan’s (which reminds me I should get that sermon online too), so my homiletical habits weren’t too rusty. And although I have a lot of other things on my mind, this sermon seemed to come together pretty smoothly. As often, I needed to let the sermon settle and my imagination detach from it a bit before I could gather it into a conclusion, but that too came out all right when I needed it. (The sermon bit is below, in the ‘Continue reading’ link.)

Our home-front unsettledness continues for another few days. After that, I’m counting on being able to let out some very deep sighs and begin relaxing.

26 May 2013

+

St. Mary’s Cathedral, Glasgow

Proverbs 8:1-4, 22-31 / Romans 5:1-5 / John 16:12-15

Jesus said to the disciples, “I still have many things to say to you, but you cannot bear them now.”

+ In Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.

Amen.

Jesus’s words to his disciples sound a somewhat poignant note in a season that we ordinarily observe with joyous celebration and doctrinal imprecision. Peter, Andrew, Nathaniel, Thaddeus, all had more to learn from Jesus in the last few twilight hours of his Judean ministry, but they could not bear what he had to teach; and we also have more to learn, but we aren’t ready for it now. For all our doogmatic deliberations, for all our spirituality and fresh missional expressions, for all our independent not-just-swallowing whatever the church catholic teaches us, we aren’t ready to hear everything Jesus has in store for us.

Why not?

Why should it be that Jesus holds the truth back from us? This is a pretty spiritually sound congregation; notorious sinners aren’t common among us, and each of us can think of holy and admirable people of God we’ve met here, saints among us even this very morning. And truth matters; if we have to wait for the truth, if Jesus judges us unready for a truth yet to come, how are we to go about our business in the interim? To what shall we bear witness if not to the truth?

When the theme concerns Jesus withholding the full truth from us, only a very unselfconsciously vain preacher would presume to explain just why Jesus holds back, and just what he is deferring for the Holy Spirit to reveal. I hope I am not that preacher.

At the same time, the deferral of truth, the non-finality of the truth that Jesus offers us in his last teachings, that provisionality itself entails a particular sort of uncertain truth. If nothing else, we learn from Jesus’s words that we ought not imagine that we have attained a degree of knowledge about God and the cosmos that would warrant dictating to others. We don’t know enough. We don’t know how we could tell if we did know enough. We do know that Jesus warned us, explicitly, that we had more truth to wait for; and we know that Paul himself, for all his confidence, frequently admitted that he himself still knew only in part. In one of my favourite passages of his letters, he reminds the Philippians

I want to know Christ and the power of his resurrection and the sharing of his sufferings by becoming like him in his death, if somehow I may attain the resurrection from the dead.

Not that I have already obtained this or have already reached the goal; but I press on to make it my own, because Christ Jesus has made me his own. Beloved, I do not consider that I have made it my own; but this one thing I do: forgetting what lies behind and straining forward to what lies ahead, I press on toward the goal….

Likewise, I have not already attained the depth of knowledge to tell others what is the mind of Christ; I cannot bear to hear that truth from him. Nor do you already know the truth; for that, we need the Holy Spirit. We need the holy Spirit, and a lot of time, an awful lot of time. More, probably, than any one of us has at our disposal.

We need the Spirit to lead us into truth, and we need time to grow into the truth that the Spirit reveals bit by bit. We need the patient endurance that equips us to listen respectfully without imposing our ideas on others, without lazily conceding that everybody is right in their own way: ‘All have won and all must have prizes’. We need the patience and discernment to attune ourselves to the way the Spirit comes to us — sometimes with Pentecostal winds and tongues of fire, sometimes with a tumult of various languages, sometimes in dreams, sometimes through the ten thousand hours of back-breaking hard work, hard prayer, hard painting, hard writing, hard kicking, hard calculating, hard gardening that bring us to the precipice of excellence. We need the ten thousand hands that hold us up, the shared patient, discerning practice of truth by which we open all our hearts to the Spirit of Truth. We aren’t born ready for that. We aren’t all ready for that. We can’t bear to hear it, yet.

Listening in on Jesus’s after-dinner discourse I feel perplexed, I feel sad for the disciples. But I recognise something about what Jesus is saying. The day that we think we have a handle on the truth, when we claim to hold it as a secure possession, when we brandish it as a club, we can be sure that the truth has eluded us. No matter how hard we try to establish the truth, to attain certainty, to determine the mind of Christ, we encounter details and differences that complicate our attempt at mastery. We can choose to ignore the details; we can override the differences; but in doing so, we’ve lost the fulness of the truth. Truth always waits for us over a horizon, in another n-dimensional space, beyond another modulation, incorporating and transcending another difference, drifting past like smoke through a fishnet. The truth is different — and by attending to the Spirit, by allowing the Spirit to lead us (rather than by us assigning the Spirit a defined place in the queue), by following the Spirit into truth, we reach deeper into the cornucopia of difference that truth comprises.

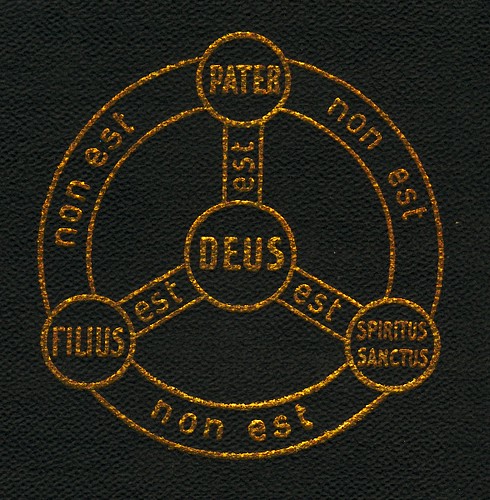

Truth is different, truth has to be different, because difference lies at the very heart of God’s own identity. The Father is different than the Son; the Son is different than the Spirit; the Spirit is different than both the Father and the Son. The One God whose faith we confess is not divided, but different. So when we sing with the Psalmist ‘Lead me in your truth’, when we listen to Jesus say ‘I am the truth’, when we ourselves pray for the knowledge of God’s truth, we prepare our hearts for something different from what we know, what we expect, what we assume.

Isaac Watts, in two of the neglected long-meter verses from his hymnody, verses that only a theology nerd could love, writes

Glory to God the Trinity,

Whose name has mysteries unknown;

In essence One, in persons Three,

A social nature, yet alone.When all our noblest powers are joined

The honours of thy name to raise,

Thy glories overmatch our mind,

And angels faint beneath the praise.

Are you ready for glories that make angels faint? I don’t think I am. I’m not ready for a truth that explodes through my expectations like a roman candle through the evening fog. I’m not ready for a revelation that displays my conclusions as riddled through with wish-fulfilment and prejudice. I’m not ready for the recognition that the Spirit of Wisdom that was with God in creation, that was daily God’s delight, has a different perspective from my own clever notions.

And from my unreadiness — perhaps from yours as well — from my unreadiness arises… hope. For if God is all and only what our theological scientists have extrapolated God to be, if we know the dimensions of the fulness of God’s greatness, the depth of God’s mercy, the expanse of God’s love to the precise millimetre, then the hoping is over; hope that is seen is not hope, for who hopes for what he already sees? Instead hope, the virtue of hope, the habit of hope, emerges as the patient, trusting, discerning wisdom that the divine difference is a difference for the better. The Spirit will take what Jesus left unsaid, and will glorify him, because the Spirit will declare Jesus’s truth to us. The revelation of the truth will come to us resplendent in glory, overmatching our mind, setting all things aright; but we cannot bear that now.

You may be as impatient as I am for the climax of the story, for the big plot twist at the end that ties up the threads that Jesus leaves loose in his teaching. That’s hope pulsing in our heartbeats, straining in our muscles, aching in our souls, growing in the daily practices by which we turns the best of our capacities toward God. Mathematicians contemplate infinities all the time; they’ve put in their ten thousand hours of preparation. Musicians already understand that deliberate harmony (and dissonance) requires both difference and unity. Painters, dancers, gardeners, parents, poets, accountants, perhaps even academic theologians attune themselves to difference and infinity through whole lives of concentrated patient attention — and perhaps even more by letting go concentration, and trusting the inferences, trusting the music, trusting the canvas, the soil, the toe shoes, the nappies, trusting the hands of the Spirit to bear us along, holding us, raising us, leading us into all the unspeakable, infinitely differentiated, gloriously harmonic truth.

Amen

Dear AKMA,

As ever I am a politely appreciative but deeply unsatisfied customer.

You did not give us, of course, what that dreadful hymn of Newman’s gave us later in the service: the trinity as talisman; an incantation against vulnerability; a dehumanized theology; Harry Potter on incense! Does no-one read the words for the music? For myself I cannot sing them.

But to cut to the chase – given that Jesus is represented as addressing the then disciples and that the point of the passage is that the Holy Spirit will lead into all truth when Jesus is gone, it can hardly be over presumptuous of subsequent preachers to take a stab at what that truth might be. Surely? Jesus does after all say “lead YOU [these actual disciples] into all truth.”

No, I suggest that the reason you shy away from doing so has nothing to do with the text and, as it should do, everything to do with our modern worries about “truth” as a category. But you don’t say this. Instead you seem to run with “truth” in an idealist sense, to keep nodding at the horizon, in the direction of the nineteenth century, when the problem of truth, and what keeps you from really addressing it, is all the water that has flowed under the bridge since we gave up on metaphysics.

You confuse things by saying in one breath that “truth is different” and then speak of the “cornucopia of difference that truth comprises.” These are quite distinct things. If truth is different then it is simply unknowable because it is never the same as what you know. This is not a helpful concept of truth.

On the other hand the “cornucopia of difference” is a synthesis of a very idealist kind. This is very confusing when you say that “truth has to be different, because difference lies at the very heart of God’s own identity.” Did you mean to say “differentiated”? But I’m not sure that helps. It is hard to see why differentiated is so different to divided. It’s all a question of how you place the parts or “qualia” in relation to one another. Of course, in the end all we have is differance.

You go on to say that you’re “not ready for a revelation that displays my conclusions as riddled through with wish-fulfilment and prejudice.” But you ARE ready! Of course you are, as we all are: because that is exactly the character that truth has for us in a post metaphysical, pragmatic age.

From this point of hesitation your sermon collapses into nostalgia: nostalgia for the old, old story; the big story; the rose-tinted hope that words like “unspeakable”, “infinitely differentiated”, “gloriously harmonic” can still mean what they used to mean.

Respectfully yours,

Chris.

Dear Chris,

I had hoped to distract you by into correcting my use of terminology from maths, but you have looked past that callow ploy to get to the heart of the matter. I will wait to respond until I’ve had a bit of time to distinguish areas where we just have divergent theologies from the areas where I articulated our possibly-convergent theologies less aptly than I ought to have. Thanks, as always, for taking the time to respond.

Grace and peace,

AKMA