This morning we all woke up way too early, and Margaret and Pip and I trundled down to DePaul so that we’d be sure to arrive in time for me to give my plenary at the Ekklesia Project Gathering. We were pretty sleepy till partway through breakfast, but by my third cup of coffee I figured I’d be able to keep my eyes open through the whole presentation.

I’ll add the transcript of the whole presentation in the (More) area; PDF available here, and an mp3 from ChuckP3 here. For casual readers and RSS, though, the short answer is that it seems to have gone well. We had some active conversation afterward, and I could spend the rest of the day relaxing and jawing with friends rather than kicking myself.

“Relaxing,” that is, until 7:15, when the presenters and I were called to the front for a panel discussion of our papers, led by Barry Harvey. Barry asked us hard questions, which struck me as decidedly unfair, given how little sleep I’d had. When the EP crowd got tired of hearing us panelists talk, Margaret and Pippa and I hastened back north to Evanston.

Within an hour, I’ll be fast asleep.

[A revised and expanded version of this talk is now available in Looking Through a Glass Bible, ed. A. K. M. Adam and Samuel Tongue (Brill, 2014). Makes a great christmas or birthday gift.]

Godliness as an Alternative to Empire

I am the LORD your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery; you shall have no other gods before me.

You shall not make for yourself an idol, whether in the form of anything that is in heaven above, or that is on the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. You shall not bow down to them or worship them; for I the LORD your God am a jealous God, punishing children for the iniquity of parents, to the third and the fourth generation of those who reject me, but showing steadfast love to the thousandth generation of those who love me and keep my commandments.

You shall not make wrongful use of the name of the LORD your God, for the LORD will not acquit anyone who misuses his name.(Exodus 20:2-7, NRSV)

Thank you, Brent and Rodney, for the invitation to talk with the Ekklesia Project this year. Every year’s Gathering encourages and refreshes me in vital ways, and I hope that by talking through some of the ground that mediates Bill Cavanaugh’s talk about theological dimensions of our imperial situation, from last night and Sylvia’s more comprehensive account of a biblical perspective on Empire, I can clear some ground where we can meet and work out concrete ways of living as godly people as a practice of resistance to an imperial context.

So, to begin a reflection on the how the Decalogue – and specifically, the first three commandments of the Decalogue – might shape us for godliness in resistance to the power of Empire, let’s re-read together the passage that Rodney assigned to me.

First, these commandments are addressed not to a nation-state, but to a bunch of people wandering around in the wilderness. The relevance of the Commandments doesn’t depend on an established civil government enacting these principles into public policy, nor on each individual adopting them as a personal code. The Commandments are addressed to a people, a particular community. And this people hold together as a people in relation to the words we’re reading.

“I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt.” God begins by announcing the Divine Name; where our careful translations say “the Lord,” the Hebrew specifies God’s own name – at which, according to the tradition1, all the world stands still, all sound is hushed, the praise of God in heaven and the mysterious wheels of the chariot cease spinning, as God pronounces the unspeakable Name. God announces the Name, and explains that God’s identity is made known in saving this people from slavery – in the words of Psalm 77, “with a strong arm God redeemed the children of Jacob and Joseph” (Ps 77:16). That point bears on a later part of my argument, but for now bear in mind that the Name itself is understood as a command in the Judaic tradition2; the bare fact of knowing God activates an ethical obligation whose details emerge in the subsequent verses.

The Lord emphasizes that this is not a random encounter between nomadic herders and a post-Chaldaic deity. As it turns out, the God who teaches Israel how to live in the Decalogue is the same God who delivered them from slavery in Egypt; God has already extended divine mercy to Israel as a basis for Israel trusting in God. “Deliverance” now constitutes a further revelation of God’s identity, so that everything else we will learn about God should cohere with the this demonstration of freedom.

“You shall have no other gods before me.” The prepositional phrase “before me” could be clearer; it could mean a variety of things, from “over against me” to “in preference to me,” but whatever the precise nuance of “before me,” the across-the-board sense is that any other allegiance must be set aside in favor of our allegiance to the Lord. Here God is not arguing that other deities don’t exist – the next commandment goes on to allow that they’re real in some sense, since God commands that we not bow down to them or worship them.3 Our allegiance to this God takes precedence over any other possible priority; any other god, any other possible rival for our commitment, must give way to the Lord God who brings us out of slavery.

The next commandment, then, goes on explicitly to require not only that the people of God commit themselves completely to the Lord, but that we follow through on that promise of loyalty. God’s unwillingness to allow anyone or anything to come intervene between God and humanity comes to expression in the commandment, “You shall not make for yourself an idol”; we may not participate in any of the plausible, popular, culturally-acceptable practices that infringe on our unique commitment to God. That rules out the obvious – making and adorning statues that depict other deities (golden calves, for instance). It further rules out such representations of the Lord God as might confuse us into worshipping the created instead of the creator, or such as satiates our imaginations with definitive details on topics where God has not seen fit to supply knowledge. Our God specifically does not want us to think that God looks like a white guy; Moses is the only person in Scripture who gets a direct glimpse of God, and even then he only sees God’s hinder parts. (Not that God’s hinder parts wouldn’t look divine.)

In a theme that resounds through all of Scripture, God consistently condemns any human endeavor that encroaches on God’s unique self-representation. The Golden Calf episode stands out as an example, not only because it displays the chosen people indulging in a festival of idolatry while Moses is on the mountain, receiving the Torah, but especially because Aaron assures the people, “These are your gods, O Israel, who brought you out of the land of Egypt” – to which God responds, “No way, Moshe.” however much the God’s people demand God on their terms, we may not arrogate to ourselves the prerogative to characterize God as suits us; we may not devise domesticated deiti-ettes to solace our longing to lay hold of holiness for our own ends with emblems of the Lord.

Sometimes the basis for our exclusive commitment to God is read as “jealousy,” as though God were a suspicious, envious figure, hiring sleazy detectives to catch us in a motel with strange gods. The jealous zeal of which Exodus speaks here is not expression of a lack – as though God were the Ricky Ricardo, calling, “Israel, you got some ’splaining to do” – but this zeal identifies God as “utterly ardent, uncompromising,” as unwilling for anything or anyone to come between God and the people God loves.4

Finally, the third commandment forbids us to invoke God for ungodly purposes. The commandment may be directed specifically against lying in general, or for swearing by God’s name in a false cause. The sense of this commandment, though, permits a broader interpretation – and its proximity to the commandment against bearing false witness in 20:16 suggests that this verse concerns something different, something more pertinent to the preceding verses. In context, that difference seems to entail claiming God’s authority for purposes that are not God’s. We are not free to profane God’s name by ascribing to God’s will, God’s wisdom, that which we intend for our own aims. Just as God won’t allow us to revere the Golden Calf or to honor it as our deliverer, so God rejects false prophets who claim “Thus says the Lord” when they themselves have devised the prophecies. Indeed, the church has appropriately discerned a further sense to this commandment in forbidding any magical use of God’s Name – whereas in many systems, possession of a god’s or a spirit’s name gives one power over that subject, the God of the Decalogue cannot be compelled by such devices.5

To summarize, then, the first three commandments articulate a theology by which we align ourselves with a God who claims priority over all other interests or motivations, whom we may not draw down from heaven in the tangible, visible form, nor may we substitute for this invisible God a more congenially accessible champion. We may not dress up our intents and purposes by wrapping them in God’s radiance. The God of the Decalogue is uniquely authoritative, cannot be fashioned after our own image (pace Feuerbach), and cannot be controlled: God is absolute, aniconic, and useless.6 God does not exist for our use. We cannot honor this God by soft-pedalling God’s uncompromising will, or by painting God in our image, or by bossing other people around in the name of God. We honor the God who brought us out of slavery into freedom by the practice of godliness, of standing firm for God.

As you may have ascertained from this description, the characteristics of the Decalogue’s God comport poorly with priorities of an empire. Whether or not, one construe the present U.S. regime as an imperial pretender, recent events point to ways in which a nation formed with a powerful ideology of the state can modulate from general respect for civil authorities to veneration of numinous national entities in a mode that challenges these commandments. The transition from dutiful respect to misplaced reverence is facilitated by a several factors. In part, people understandably long for a more available God, a God whom one can rally to urgent causes. In part, such a transition serves the interests of the state. Some part of the transition serves other interests. However one distributes the causes, they combine to engender an atmosphere in which the state draws to itself allegiance, iconic sanctity, and effectuality that properly pertain only to the Lord.

I’ll concentrate on the U.S. in the following examples. That’s not because I think the U.S. is unique, or that this is the worst offender; it’s because I’m better acquainted with public discourse in the U.S., and the illustrations are so poignant.

So let your memories drift back to 2002, when a panel from the 9th Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals ruled in the case of Newdow vs. the U.S. Congress. The 9th Circuit determined that state-sponsored recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance in public schools violated the establishment clause; it’s impossible, they reasoned, to identify the U.S. as a nation “under God” without promoting a religious agenda. Politicians of almost every stripe rushed to demonstrate their pious patriotism by insisting that professing loyalty to “one nation, under God” need not conflict with the Constitution’s insistence against any “law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” Positions ranged from the embarrassing de minimis claim that such a short phrase couldn’t do any ideological harm – it didn’t mean much of anything (which provokes the question, “Why then include it?”) – to overwhelming votes in the House and Senate to the effect that the words “under God” ought to be retained in the Pledge, anyway.

My theological complaint doesn’t rest on any of those grounds (though I’ll admit to being grieved that anyone would argue that public affirmation of a transcendent God doesn’t mean enough to give offense to an atheist). Rather, I want to call attention to the oddity that so many Jews and Christians were advocating a pledge of allegiance to a national flag. The U.S. flag stands in a direct line of descent from the insignias, emblems, and standards by which nations invoked totemic deities in battle, so that two millennia ago, faithful believers were willing to lay down their lives rather than venerate, or even tolerate, these representations of rival gods. Tertullian rejected the regimental standards as “rivals of Christ”7; and when a Roman procurator brought flags that honored Caesar into the city of Jerusalem – not into the Temple, mind you, but just in the city limits – a crowd of Judeans staged a five-day demonstration to have the standards removed; and when that procurator threatened to execute them, they volunteered to be killed, rather than permit these idolatrous emblems to remain within the city of Jerusalem.8

Now, we concede without hesitation that the policies of the Roman Empire entailed a pervasive paganism inimical to Judaism and Christianity. Nonetheless, Pontius Pilate was not asking the Jerusalemites to pledge allegiance to the standards; yet the people resisted the very existence of the iconic representation of imperial power within the holy city. In the twenty-first century, on the other hand, a unanimous vote of the U.S. Senate affirmed the premise that U.S. Christians ought to pledge their allegiance to the flag, and to the republic for which it stands.

Several weeks ago, as though our legislators were afraid that I wouldn’t have sufficient material for this talk, the House of Representatives passed a proposed amendment to the Constitution that reads, “The Congress shall have power to prohibit the physical desecration of the flag of the United States.” I want to call your attention to the one word “desecration,” for that word distinguishes the amendment from merely debatable prohibitions of unwelcome political expression. This amendment, however, presupposes that the flag of the United States is in some sense sacred; and that claim of sanctity stands diametrically opposed to the teaching of the Decalogue, as the citizens of Jerusalem knew, as Christian conscripts into the Roman army knew.

It will be said that the flag’s sanctity is figurative: “Of course no one regards the flag as the symbol of a transcendent divine national entity, and the flag doesn’t signify the genius of the President or the totemic protector of an army division.” But a figure of speech is never simply a figure, never just a metaphor. As it turns out, the vehemence with which politicians leapt to defend the state’s interest in inculcating obedient allegiance to the flag, and to define the flag as a sacred object that one might be punished for treating impiously, bespeaks a more than merely metaphorical sensitivity at this point. One need not alter the Constitution to justify a metaphor.

As the priorities of civil powers have permeated U.S. Christianity, it becomes harder and harder to make a theological case against the imperial ethos. The church feels a powerful temptation to accommodate, indeed in some quarters even embrace, the image of the United States as an visible, effective anointed agent for realizing divine purposes. In the name of realism, in the name of deference to honoring those who bear the effects of war (effects that our everyday language reveals that we regard as a sacrifice9), strident voices demand that Christians profess their loyalty to a national ensign, and observe the festivals that the government establishes as though they were feasts of holy martyrs. The combined interests and sensitivities – often innocent, often commendable – of state power, of patriotic citizens, of injured families, and of corporate advantage converge in an ambiance I will call Sacramerica.10 In Sacramerica, the national pride of the United States blossoms into a displaced messianic hope that subordinates the God of the Decalogue to the sentimental consolations and pragmatic policy interests of a vast congregation of baseball fans, apple-pie eaters, and fireworks admirers.

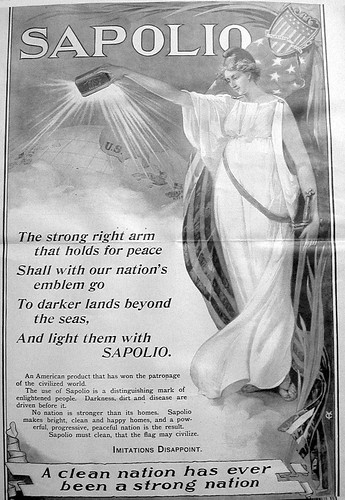

Lest you think that my rhetoric has carried me too far, and lest the tone of this presentation grow too grim, I’d like to call your attention to a handout from a century ago. This handout richly rewards our critical attention, and vividly illustrates my claim that Sacramerica constitutes a spiritual alternative to the God of the Decalogue.

This illustration comes from an advertising campaign originated by Artemis Ward, one of the pioneers of the modern advertising industry. Ward made Sapolio a brand name second only to Ford in popular recognition and cultural currency11 by publicity stunts, jingles, mass-transit placards, and full-page advertisements in literary magazines. One such advertisement found its way into Margaret’s and my private collection several years ago.

How does this advertisement serve my point? Let me count the ways. Being a biblical student, I’ll start by commenting on the words. First, then, “the strong right arm that holds for peace” in this poster belongs not to the God of peace who redeemed the children of Jacob and Joseph, but to Lady Liberty. The ad seems to identify the inhabitants of the Philippines, Cuba, and Puerto Rico at the turn of the twentieth century as “dark,” “dirty,” and “uncivilized” relative to the United States; Sapolio and the U.S.A., it suggests, will take care of that with their cleansing, civilizing imperial mission. The copy warns us that “imitations disappoint,” or as Moses might have said, “Thou shalt have no soap before me.”

The iconography of the advertisement speaks even more emphatically of Sacramerican displacement of God. Here Lady Liberty, carrying a sword, draped in a flag, enlightens the world with her bar of soap. The world as Sapolio imagines it constitutes only the U.S. and three of its colonies – Mexico (which is almost the same area as Cuba) vanishes into the ocean, and Canada doesn’t exist (not to mention Europe, Asia, or Central and South America). This American idol portrays the self-image of the U.S. projected to a heavenly scale; this is the god that Feuerbach and Durkheim warned you about. Lady Liberty wears a Phrygian cap, the vestigial signifier of the Mithraic mysteries. Any other features of the advertisement strike you?

If anyone thinks that the religious infrastructure of this ad is simply incidental, they may want to consider such other Sapolio advertisements as that placed in the Century magazine of 1904 which links Sapolio with the “very peculiar, very strict” 6,000-year-old ceremonial law of the Hebrew race. Thus it declares Sapolio “kosher” – in English and in Hebrew characters.12

It’s a measure of how thoroughly Sacramerica is ascendant in our culture that an advertisement that represents a superhuman figure that bestows light and health to a chosen people while attired in the garb of a participant in a mystery cult doesn’t strike us as odd. The point isn’t that anyone would explicitly endorse a claim that the personified ablutionary regime of U.S. commercial imperialism should be worshipped as God. The point is that an advertiser could confidently invoke an image that comprehensively displaces the God of the Decalogue, without fear that U.S. Christians would take offense, without expecting that displacement to hurt his sales.13 In an atmosphere like this, how can one proclaim the Decalogue so as to bring into focus the antithesis of Sacramerica with God’s unique, aniconic, useless identity?

Whatever else we do – and this project certainly brings together intensely creative, ingenious cultural activists – we need to take seriously the extent to which Sacramerica names not just a set of pernicious assumptions about the U.S.’s role as liberator, law-giver, and commercial agent to the world. More than that, Sacramerica names a signifying practice, a repertoire of premises and especially actions that express, affirm, reinforce, and disseminate particular sorts of meaning. To the extent that our lives do not differ perceptibly from the lives of convinced advocates of U.S. exceptionalism, the rest of the world will justifiably number us among those advocates.

What do I mean when I use the term “signifying practice”? I’m drawing that term from the disciplines of semiotics and cultural criticism, where it points to ways that people express important claims about themselves and the world not only by talking or writing, but by the ways they behave, by the ways they interact with others. It’s what we called “living signs” in our worship yesterday afternoon. Cultures, subcultures, dominant and resistant groups articulate their identities in the ways that people dress, the ways that people address one another, the type of cars they drive or their decision to ride a bicycle or take the El. We can take the example of religious vocations as a highly-visible signifying practice, wherein every article of clothing, every meal, every prayer, every gesture combine to express a particular kind of life given over to the praise and service of God. More often, though, we participate in signification less self-consciously, more by elective affiliation, with much less formal expectations and obligations; in so doing, we float along with the significations made available by mass culture and socially-dominant institutions.

Thus, when I say that we should recognize Sacramerica as a “signifying practice,” I mean that it amounts to more than a set of explicit verbal claims about the U.S. and its manifest destiny. As a signifying practice, it entails a certain confluence of patriotism, political theory, messianic hope, personal and corporate interest, and historic loyalties that go beyond arguable claims that this nation should exercise its wealth and military power in this or that way; it includes the axiom that one must vote, that liberal democracy constitutes a political order unexceptionably superior to other alternatives, that the way to resolve all conflicts is to hold a vote of some sort, hence that being right in the world should be correlative to winning, and since winning depends on out-numbering the wrong people (as Bill pointed out yesterday, the God of the Bible seems almost always to favor the smaller number), we get a persistent fascination with the number of members in churches, the number of votes for or against the denominational legislation Lillian mentioned in her sermon yesterday, and so on.

In this sense, then, I suggest that we need to take Sacramerica seriously as a cultural system. People really commit themselves to live (and die!) for the American Way. We don’t undermine that whole system of assumptions and the practices that express and reinforce Sacramerican beliefs simply by talking. To return to the Decalogue, it’s all very well for those of us who preach to devise fine sermons about national idolatry, on corporate idolatry, and on our sinful proclivity to suppose that we can sanctify our mortal purposes by invoking God’s Name over them often enough. But leaders who put their trust in the size of their armies, who believe they will be delivered by their great strength, don’t think of themselves as worshippers of Mars; they aren’t likely to acknowledge that they’ve put their faith in a god of war. And besides, when one of the most popular shows on television is candidly named “American Idol,” who’s going to balk at a little idolatry in a good cause?14 (When Margaret and I were at a conference last summer, we saw a cosmetics poster urging shoppers to “Be Your Own Idol.” It’s hard to think that’s promising sign.)

In order resist the signifying system of Sacramerica, I propose that we need to begin the work, the practice, of imagining our discipleship as an antithetical signifying practice, a practice of living in a way that throws Sacramerica off-step, out of balance.15 Now we could undertake a practice of resisting the dominant culture in the name of a new, better dominant culture – but that’s a trap. That invites us to construct Sacrekklesia or Sacramergent in the place of Sacramerica. Instead, I want to suggest a placeholder for signifying practices in resistance, and that placeholder rubric is “godliness.” I suggest that we aim at godliness (partly, of course, in response to Sapolio’s offer of cleanliness, but also) partly because this catches some of the pivotal importance of God’s identity as it’s revealed in the Decalogue; we ought to live in ways that bespeak the uniquely authoritative, aniconic, useless God of whom the commandments teach. Moreover, “godliness” gives us a target that’s harder for Sacramerica to explain away. If we target “justice” or “freedom” or “openness” as the characteristics of our people, the dominant culture can comfortably ignore us; they know all about justice and freedom and openness, and our protests that “that’s not what we mean by justice” or “that’s not true freedom” will fall on deaf ears. But godliness names a characteristic that the nation-state cannot as readily simulate and co-opt; we have a few more seconds of a fighting chance to define our own terms.

The number of possible syncopations we could throw at the imperial ethos of the commercial U.S. mission obviously exceeds my capacity to catalogue this morning, and (less obviously) exceeds my imagination. Moreover, if I were to propose one or two practices, probably practices at which I have some experience, I might make myself out an exemplary resister – but in the interest of binding this theoretical account to more concrete realizations of it, I’ll venture that risk here.

How might we activate a signifying practice of godliness? I’ll throw out a few suggestions, not expecting that my suggestions carry any authority just ’cos I’m standing up front of the gathering, but hoping that you’ll call up better, more winsome ideas. So here are some ways we might enact our signifying practice of Decalogical discipleship:

+ Not voting. Suggest not voting to a Sacramerican, and watch the explosions.

+ Home schooling, only not because you’re worried about evolution

+ Holy dying, to learn how gracefully let go of that gift in hand that we will eventually have to exchange for an inconceivably greater gift

+ Sell your cars. All of them.

+ Eat intentionally – vegan, vegetarian, eating only local produce perhaps

+ Other ideas that you all will suggest in the conversation time16

Life under Empire gets disorienting and disheartening. The Decalogue helps remind us why, because in the light to the Decalogue we see more clearly the differences between God and idols, between the empty Shrine and the empty tomb. If we keep covenant with the God of the Decalogue by shaping our lives to testify to the God of the Decalogue in contrast to Sacramerica or any other rival deity, we will have done what God requires of us – and we can gather, an imperfect but faithful body, to pray together the words of Thomas Cranmer: Lord, have mercy upon us, and incline our hearts to keep this law.

+++++++++++++

I’ll add notes later; tomorrow, maybe.

Gee, if I had know you’d be making a pdf doc available I wouldn’t have taken notes. Thanks for your insight this morning on concrete practices the Church can use to resist Sacramerica. And the conversation on public schooling was new to my ears but very helpful. I am not a father yet but it gave me something to think about.

Kaz

Much blog fodder and great stuff here. I’m so glad you were there to give this perspective and insight on the Decalogue. it was truly inspiring for me. I blogged several entries in th past hour as I read and listened.

To a layman whose sense of the resonance of some of these citations may be faulty, what is striking is the apparent tension between the course of deployed syncopation outlined above and this comment of yours, nearby in your blog, which I found very moving:

We demonstrate sinfully constricted imaginations when we concentrate our efforts on prevailing over our sisters and brothers, arm-twisting or out-maneuvering in order to win, to justify oneself.

To a fine reader, I appeal with the following distinction — hoping that it does not seem egregious special pleading:

When in my EP presentation I suggest that dedicated practitioners of the Decalogue discern paralogical ways of living out their faith, I do so not from any interest in triumphing over Sacramerica, or compelling other people to adopt a more “ekklesial” way of life. I advocate this sort of practice-of-resistance as a way of keeping-conscious of one’s identity and as a way of inviting others to observe and discern whether the way we live might constitute a more satisfactory way for themselves.

glad this is online. I heard you give the presentation at EP, but I am glad you put this on the site.

I am going to link disseminary at jesusradicals.

peace

andy