Really, This Is About Jonah

I’m supposed to be working on my sermon this morning, and (in a sense) I am, since by blogging these thoughts out, I’ll make room in my imagination for the sermon to coalesce. As I was reading for course prep yesterday, my iPhone played XTC’s “No Language In Our Lungs,” one of my all-time favorite musical ruminations on hermeneutics (lyrics):

There is no language in our lungs

to tell the world just how we feel

no bridge of thought

no mental link

no letting out just what you think

there is no language in our lungs

there is no muscle in our tongues

to tell the world what’s in our hearts

no we’re leaving nothing

just chiselled stones

no chance to speak before we’re bones

there is no muscle in our tongues

I thought I had the whole world in my mouth

I thought I could say what I wanted to say

For a second that thought became a sword in my hand

I could slay any problem that would stand in my way

I felt just like a crusader

Lionheart, a Holy Land invader

but nobody can say what they really mean to say and

the impotency of speech came up and hit me that day and

I would have made this instrumental

but the words got in the way

there is no language in our…

there is no language in our lungs

to tell the world what’s in our hearts

no we’re leaving nothing behind

just chiselled stones

no chance to speak before we’re bones

there is no language in our lungs.

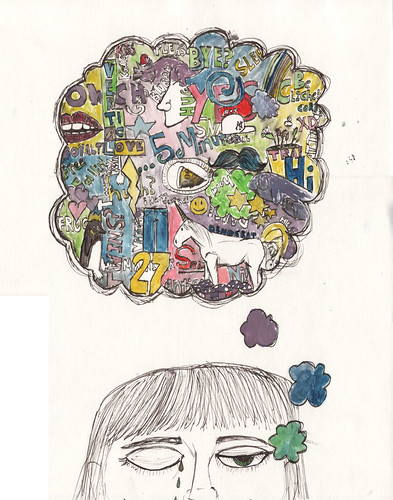

Andy Partridge suggests (“suggested,” since the song comes from 1980) much of what I’ve been advocating in the past few books and essays. “Meaning” isn’t something in there, whether in words or in us; we can’t transmit intentions in such a way as to make a warrantable connection between speaker and receiver. The urgent temptation to think and act as though our expressions contain definite meanings undergirds the outlook of interpreters who want to be able to oblige others to adopt “correct” understandings, to suppress the abundance of meaning that any expression might engender.

All this came to mind as I was reading Richard Hays’s study on Paul’s use of the Old Testament, wherein Hays frames his arguments with claims about what Paul was alluding to, and what we can infer from his allusions. Now, on the whole I tend to agree with Hays’s supposition that Paul’s allusions to Scripture should most productively be read with attention to the material surrounding his explicit citation, so that we catch points of reference that Paul didn’t include in the quoted material. But sometimes Hays infers that because Paul constructed such an allusion, he must have expected his readers to catch it — and that seems a very different, and very mistaken, inference. Writers and speakers construct our expressions out of the abundance of our imaginations (deliberately and subconsciously), but experience teaches us that people do not always catch all our allusions, and our expression is (oddly) the richer for not being comprehensively up-taken.