(The page that originally housed this essay — http://www.seabury.edu/faculty/akma/Notbible.html — has been deleted from the Seabury-Western web servers. This page reproduces the text of that essay.)

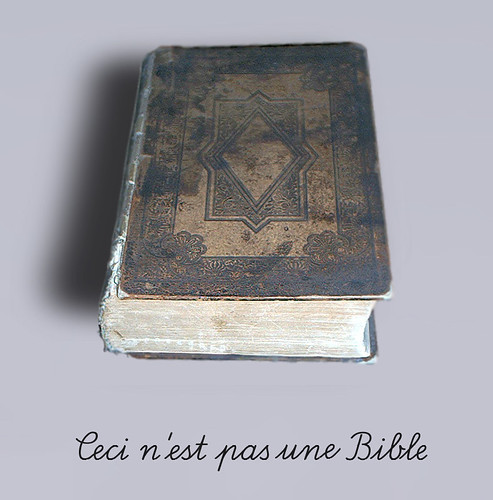

This is Not a Bible

Dispelling the Mystique of Words for the Future of Biblical Interpretation

A. K. M. Adam

University of Oxford

© American Bible Society

At this point, projections based on the present are worse than useless. And that, of course, is exactly how matters stand at the turn of the millennium when it comes to technology. We’ve never experienced a period of such rapid change—especially when it comes to the Web. Making predictions in this kind of environment isn’t just foolhardy; it can be a kind of denial. “Tomorrow will be much like today”—yeah, you wish!

— David Weinberger

He spent some time with the holoscope, studying Elias’s most precious possession: the Bible expressed as layers at different depths within the hologram, each layer according to age. The total structure of Scripture formed, then, a three-dimensional cosmos that could be viewed from any angle and its contents read. According to the tilt of the axis of observation, differing messages could be extracted. Thus Scripture yielded up an infinitude of knowledge that ceaselessly changed. It became a wondrous work of art, beautiful to the eye, and incredible in its pulsations of color.

— Philip K. Dick, The Divine Invasion, 65-66.

What is “the present” for biblical scholarship? The present typically involves attaining fluency (or, more realistically, reading competence) in a variety of languages; inculturation in the somewhat parochial world of academic biblical studies; and immersion in the vast secondary literature that the biblical-criticism industry continually generates. The present focuses acute attention on words, the words that comprise our Bibles and the words with which we represent those (biblical) words.

What does the future—especially the future of cybermedia—hold for academic biblical scholarship? I am less foolhardy than the many prognosticators who can assert with confidence the ramifications of the World-Wide Web, hypertext, digital video, streamed audio and video, and digital publishing (to name but a few media convulsions that bear on the future of biblical scholarship). After all, who would have understood the ramifications Europe’s discovery of movable type when the first Bibles were printed on Gutenberg’s press? Whatever specific changes develop over the years to come, the advent of electronic media will catalyze a complex of circumstances that biblical scholars in the age of printing have successfully avoided so far (even in the face of film and video media), and the dimensions of these new domains of biblical interpretation can not be estimated on the basis of the way things are right now.

Those who espouse detailed predictions of the discipline’s future remind me of a scene from my elementary-school education. A number of my childhood’s classrooms featured tall rolling gantries that held television sets, televisions that were ostensibly available to usher me into the brave new world of broadcast education. As I recall, we occasionally watched a weekly science program, and once a year may have seen a televised version of a great book or play, but almost as often the sets were used to watch the Pittsburgh Pirates’ baseball games. The cost of those large-screen sets per instructional hour of use must have been enormous; and the cost per effective hour of use was vastly greater. Someone had imagined that the future of pedagogy lay in class-period-length instructional programming on “educational” broadcast channels, and the Board of Education had invested in that vision of the future only to encounter the reality that there were few instructional programs to watch, the programs available did not necessarily match the instructional schedule of every elementary school in the city, and many of the programs simply showed in two-dimensional black-and-white pixels what our science teacher could have shown us in three-dimensional, colorful flesh.

Unduly specific predictions about the future of biblical studies in an intellectual economy shaped by cybermedia risk the dusty fate of my elementary-school television sets. As David Weinberger points out, when conditions are changing rapidly, predictions are a risky business. Especially when the rate of change is exceptionally rapid, when the very categories of change are themselves changing, we are wiser to wait and see what happens than to invest our resources in one particular version of what will surely come tomorrow—no matter how firmly that anticipated future is asserted, no matter how roundly it is endorsed. Our waiting need not be idle, however; patience affords us the opportunity to prepare for the changes that will be borne upon us by weaning ourselves from some of the constants that define the status quo. Recognizing some elements of the present as transitory effects of a changing disciplinary field, we can equip ourselves to pursue biblical studies differently as the field modulates around us.

With a view to the relation of biblical interpretation to cybermedia, then, I propose two propaedeutic recuperations: first, a demystification of words as means of communication, and second, a relaxation of what has been the constitutive hostility of modern academic biblical studies to allegory. At the heart of both these proposals lies a sensitivity to the explosive breadth of means for communicating information in cyberspace. Academic biblical scholars need to awaken to a range of communicative practices that extends far beyond the print media in which we typically subsist; one might well ask, “If a picture is worth a thousand words, why can’t we have more illustrations and fewer multivolume sets in our commentaries?” Once we admit a richer span of communicative options, however, we will need an articulate mode of criticizing these representations, and it is for this purpose that learning some lessons from allegorical interpretation may better equip us for future interpretive ventures.

Demystifying the Word(s)

The circumstances most liable to change in our future resist precise articulation, in part because they are effects of the structure of biblical scholarship as academic institutions have defined it. The discipline of biblical studies has grown up at the intersection of divergent, often conflicting, forces driven by theological interests, secular academic interests, and the broad cultural currents of nineteenth- and twentieth-century European and American modernity. The confluence and divergence of these formative influences has produced an academic field whose central practices and guiding metaphors derive from a particular model of translation. The academic biblical scholar’s job of work allows and requires him or her telling an audience what the Bible means, how the texts written in ancient Hebrew and Aramaic, and in Hellenistic Greek should be expressed in contemporary European and American vernaculars. Unfortunately, practitioners of academic biblical scholarship do not usually appreciate the wisdom of scholars in the field of translation (whose practical emphasis itself sometimes occludes other interpretive problems—problems of theoretical hermeneutics that biblical scholars have been dealing with, or hiding from, for centuries). Instead of benefiting from the work of theoreticians and practitioners of translation, academic biblical scholarship tends shows a persistent inclination toward a fantasy of a perfect one-word-to-one-word equivalence.

Even the goal of “fidelity” to the biblical text, the hallmark of the Bible Society’s ceaseless efforts to bring the Bible to all audiences, can sometimes be haunted by the perfect-translation fantasy. A rich notion of “fidelity” embraces far more than grammar and lexicography, but when a particular paraphrase or a new-media representation of a biblical passage dissatisfies its critical readers, they are apt to attribute their frustration to the “freeness” of the paraphrase, or the remoteness of the video production from the biblical text. We should, however, distinguish the matter of “free paraphrase” or of the metaphorical distance between two media from the matter of “fidelity”; as translators have long known, one may sometimes attain the greatest fidelity to a biblical expression only by a very free paraphrase, and one might argue that passages from Ezekiel or Revelation are more effectively communicated with images than with words.

One powerful constituent in the problem of biblical studies’ past and future lies in the persistent mystification of verbal communication, which practitioners of biblical studies often reduce to communication in print (as though there were no noteworthy distinction between oral words, hand-written words, and printed words). Scholars collaborate in perpetuating a myth that (printed) words are a unique, semi-divine product with unearthly qualities. Because (printed) words do such an admirable job of facilitating communication, scholars have often jumped to the conclusion that words must possess special properties that constitute them as a uniquely appropriate medium for expression, imbued with “meaning” in something of the way that scientists once believed that combustible materials were imbued with a fiery essence, or that soporifics contained a dormitive property. If words work, these scholars reason, they must work on the basis of intrinsic meanings.

The mystique of words derives further currency from theological reasoning. The first verse of John’s Gospel, the opening verses of Genesis, the genre of prophetic oracles and the principal modes of Jesus’ teaching (particularly his teaching in parables) seem to mark verbal communication as God’s communicative medium of choice. The proposition that God’s choice to make known the record of divine truth in verbal form, as writing, Scripture, η Βιβλος, then seems to warrant our regarding words as miniature vessels of potential revelation (whereas inductions from non-verbal visual phenomena, from sublime sound or heady scent, can be dismissed as forms of “natural theology”).

To the contrary, however, words—spoken or written or printed—are not the unique vessels of meaning that our interpretive practices often imply them to be (even when we do not adhere to that premise self-consciously or explicitly). Not only words, but also physical gestures, non-verbal sounds, images, even smells convey meaning in ways different from, but associated with, linguistic expression. Our hermeneutics, preoccupied with the fantasy of the perfect translation, concentrate almost to the point of exclusivity upon words. Indeed, we concentrate not simply on words, but devote most of our attention to printed words.

Be it conceded right away that language has proven an inestimably versatile and effective means of communication. When my children have fallen asleep, I can often manage to make my ideas evident to my wife in gesticulation and grimace without spoken words, but I do not propose that words are a bad idea and should be abandoned, or that they are so radically ambiguous as to be indistinguishable from cubist paintings or thrash rock’n’roll. Words have made possible tremendous, powerful, convincing, highly-effective acts of communication. Indeed, we who are profoundly (decisively?) shaped by the effects of language can hardly imagine the scope and force of words’ influence on every aspect of human life. Neither I nor anyone I know wishes to undervalue linguistic communication.

At the same time, I do not wish to overvalue language, ascribing to it mystical properties that go beyond the social conventions that give it currency. Communication does not depend on spoken or written language (“written” in the sense of spelled-out words). One can effect understanding on the basis of gestures, pictures, inarticulate sounds. If one allows a background dependence on language (as language itself generally depends on some sensuous acquaintance with the phenomenal world)—then communication can get on quite well without explicit recourse to verbal language, as speakers of sign language can testify. Drivers cannot usually speak directly to one another, but they find ways of communicating with car horns, gestures, and startling automotive maneuvers, and internationally-recognized symbols guide drivers’ navigation in areas where they do not understand the local language. Words form an extraordinarily strong, labile, productive medium for the social interactions that sustain meaningful connections among (other) words, images, sounds, experiences—but we need not posit the necessity of verbal language for such social connections. Some social conventions can sustain some associations of meaning and experience even in the absence of verbal language.

That is to say, the argument that the success with which humans often use words to communicate does not imply that words constitute the quintessence of communication. Words prove especially useful for communicating particular kinds of information under particular circumstances, but their outstanding usefulness does not make an argument for their necessity. Neither ought we conclude that words provide a paradigmatic mode of communication, so that our theories of interpretation need only account for words in order to claim completeness. Once we entertain seriously the possibility that legitmate interpretation may involve more than providing word-for-word alternatives, the power and the prominence of non-verbal communication oblige us to offer theories of interpretation that do not treat non-verbal interpretation as an incomplete, insufficient, primitive, non-scholarly offshoot of the (verbal) real thing. A hermeneutic that works only for words is itself incomplete and insufficient.

Nor does the theological argument for treating words as the paradigmatic instance of communication carry decisive weight. Though the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, the Word was not manifest as a part of speech or a siglum; the Word effected communion with humanity by becoming human, not by becoming an inscription. The Bible foregrounds instances of verbal communication from God, but reports a variety of other means by which God makes the divine will known. God communicates not exclusively through (evidently) verbal communication, but also through visions and through physical demonstrations, and one would be foolhardy who determined that God might not communicate in yet other ways. The prophets received visions as well as verbal bulletins, and God commanded that they pass along their divine messages by physically-enacted communication. Paul insists that the created order itself communicates something of God’s identity in Romans 1. Indeed, even those who construe the word logos in John’s Prologue flatly as “word” oversimplify the semantic breadth of the term in Greek (as its common Hebrew partner, dabar, likewise covers much more semantic terrain than just “word”). This caveat applies all the more since John deploys the term in a setting that lacks the contextual markers that might tend sharply to limit plausible construals of that noun. The doctrine of the incarnation itself should serve as a warning that exclusively verbal revelation was not sufficient in itself; God chose body English, as it were, as the medium for the fullness of communication. Where Protestant theologies—which in some instances show a marked aversion to physical or sensuous dimensions of human life, preferring abstractions, thoughts, and words to images, matter, and action—prospered with the advent of printed communication and widespread literacy, other traditions have maintained the theological importance of communication in visual arts, in physical movement, in sound and smell and taste. While arguments for emphasizing verbal communication identify a legitimate strand of biblical and theological reflection, words should not be permitted to eclipse iconic, active, aural, olfactory, gustatory, and tactile aspects of theological discourse.

If we dispense with the mystical-vessel model of verbal meaning, we are not bereft of resources for explaining the relative stability of literary understanding, nor the effectiveness of verbal communication. Proponents of “meaning” often construct the hermeneutical alternatives only as: either “words have meanings” or “any word can mean any thing.” This illegitimately excludes a pivotal range of middle terms that provide quite adequate accounts of communication. The social conventions that undergird communication are strong, deep, and quite elastic (though not infinitely so). In most regards words are indeed more stable and effective a means of communication than other media. Other means of communication, however, have benefits of their own, as traffic signs, musical compositions, and fine cooking (or to remain in the sphere of theological practice, church architecture, hymnody, incense, the elements of communion, and even pot-luck suppers) all demonstrate.

Scholars have become accustomed to fixating so unwaveringly on words that they will espouse theories whose shakiness could readily be brought to light by framing them graphically. To choose a simple, common example, New Testament scholars frequently draw exegetical conclusions about the relative dates of documents or sayings by assaying the christologies that the texts reflect, or the degree to which the texts show concern about the delay of the parousia. Such reasoning might be represented graphically by the charts in the accompanying figure. In each case, as a document’s christology moves toward a more exalted understanding of Christ, or as it shows a greater degree of anxiety over the return of the Lord, that document may be presumed to date from a later period.

Of course, scholars feel free to fudge their relation to these (presupposed) charts; if a document that scholars feel strongly to date from the late first century shows robust confidence that the Lord will come soon, said scholars can point out that the apparent confidence is intended to allay the fears of the community to which the text is addressed. If a late document includes a passage that evinces a low christology, the passage in question may be an older tradition that the editors included intact. Conversely, if an early text shows signs of a high christology, we may conclude that a later editor has emended the document.

Few scholars would uphold so bald a presentation of their reasoning. The heuristic value of christology or Parusieverzögerung for dating New Testament texts presumably complements other, more rigorous criteria. Yet anyone who looks at the graphs that accompany this page and thinks hard about the geographical, theological, and cultural diversity that characterize the earliest years of the Christian movement must recognize how tenuous such criteria must be; any assumptions about a predictable correlation between chronology and either christology or eschatology stand to falsify or mislead historical reason at least as much as they stand to aid it. A Galilean from whom Jesus of Nazareth exorcised a persistent demonic presence would probably hold to a higher christology than a casual bystander who overheard snippets of a parabolic discourse, though both lived and reported their impressions of Jesus at the same time. A wandering Christian prophet might proclaim the nearness of the Day of the Lord just across town from a corner where a sage Christian teacher offered aphoristic counsel on how to live wisely and long.

The charts in the illustration are, of course, oversimplifications of more complex hypotheses. If one wanted to represent these hypotheses more fairly, one might, for instance, allow that anxiety over the delayed parousia was not a linear but a parabolic function. Or one might plot christology against years in a scatter-chart, allowing for greater variability in the distribution of data. Then, however, one would run into the difficulty that scholars assign dates to the documents in question largely on the basis of the hypotheses that we are illustrating. The data points don’t scatter much, because they have to a great extent been located with reference to the assumed validity of the hypothesis. While we can observe patterns of transition from one sort of outlook to another, the variety of particular circumstances and of human responses to those circumstances preclude our vesting the patterns we observe with the regularity that could undergird deductions about when or where or why. Sometimes visual representation of a hypothesis helps clarify just what the hypothesis entails, and how much credit that hypothesis deserves.

The question of visual representation, however, reaches beyond the value of interpreting historical-critical data and hypotheses with graphs or charts. Words are themselves sensuous phenomena, whether aural or visual. A word written is not simply the same as a word printed. A word printed in Bembo type is not simply the same as a word printed in Cooper Poster or Comic Sans. Will the Journal of Biblical Literature ever adopt a hard-to-read, grungy typeface as its standard? The way one presents a verbal message casts the message in a particular light; those who have read applications for college admission or a job opening will have to acknowledge that not all words are presented equally—a point that fueled the transition from typewriting to computer word processing, from impact printers to laser and inkjet printers.

Words signify, in other words, not only by the letters that constitute the word, or by the meaning that we conventionally associate with the word, but also by the appearance of the word—and the visual context within which that word appears. René Magritte, the master-teacher of the paradoxes of interpretation, wrought a career of painted and printed essays on just this aspect of the relation of words to images. He is best known for such works as “L’usage de la parole I” (“The Use of Words I”), a painting that combines the large painted image of a pipe with the written legend, “Ceci n’est pas un pipe” (“This is not a pipe”). The painting reminds viewers that the painting is not a pipe; it is a two-dimensional representation, significantly enlarged, of a three-dimensional implement. Further, the painting may prompt viewers to recognize that the words “un pipe” (and the demonstrative “Ceci“) are not a pipe, either. Verbal language and graphic illustrations offer two means for representing objects, concepts, and relations, but these media do not escape their status as representations.

In a less well-known article for La révolution surréaliste in 1929—at about the same time he was painting “L’usage de la parole I”—Magritte sketched an eighteen-part essay on the relation of words and images. The essay comprises small line drawings, each with a caption positing a theoretical-interpretive point. The first, for example, shows the shape of a small leaf with the label, “le canon“; of this, Magritte observes, “An object does not belong to its name to such an extent that one couldn’t find it another that suits it better” (Magritte, 60; all translations from this article are my own). Another drawing shows a human profile between the letters “a, b,” and “n, o,” which in their turn are followed by the perspective drawing of a rectangular solid: “In a painting, the words are of the same substance as the images.” In yet another, Magritte reminds his reader that “An object never serves the same purpose as its name or its image.” The essay challenges a reader’s propensity to think of words as ontologically distinct from images, as possessing intrinsic properties associating themselves with their referents or rendering them particularly efficacious for interpretation. Had Magritte been particularly interested in biblical interpretation, he might seventy years ago have begun reminding his readers of the long-standing tradition of interpretation in statuary, in stained glass, in woodcuts, in icons; our sense of the breadth of biblical interpretation might already have extended to cope not only with Milton, Mozart, Doré, and Eichenberg, but also to Dali, DeMille, and Lloyd Webber (and in a more modest way, theologian/cartoonist Fred Sanders).

Observers sometimes suggest that our disciplinary constrictions arise from biblical scholars’ “linear thinking,” from our being “too linear.” If by “linear” one means “logical” or “analytic,” the accusation probably does not hold water. If on the other hand the accusation means “captive to one-dimensional approaches to multidimensional problems,” then the accusation is demonstrably false. At least thirty or forty years ago, biblical scholars attained two-dimensionality by recognizing the legitimacy of such approaches as literary, sociological, political, and certain postmodern criticisms. The residual problem lies in the extent to which our two-dimensionality underachieves in a world of polydimensional communication; in that sense, we are not too linear but too planar. Biblical scholars have been able to finesse this limitation by emphasizing verbal communication in our main areas of productivity (our orientation toward verbal communication, in articles, books, the oral presentation of papers, and so on) and in our industrial by-products (biblical theology and preaching, each imagined as a subordinate discipline to the regnant critical methodocracy). Like inhabitants of Edwin Abbott’s Flatland, we construe the limitations of our imagination and experience as limitations of what can be imagined. Our evasive maneuvers, however, will not keep cybermedia at bay much longer, and our planar interpretive consciousness will be flung—prepared or unprepared—into a polydimensional interpretive cosmos.

When we contemplate the kinds of differences that the future of electronic media will bear upon us, we can see all the more clearly the importance of learning how to relativize the importance of words in our disciplinary practice. It takes no Nostradamus to notice that the means of producing digital video and animations have come more readily and more inexpensively into the hands of non-professionals, and that the tools available to professionals have become vastly more powerful. As the vacation slide show moved over to make room for family videotape presentations when the price of videotape cameras diminished to fit the budget of bourgeois Europeans and Americans, so the diminishing cost and complication of digital video production will in all likelihood increase the amount of information we encounter in that medium. By the same token, the most sophisticated examples of digital-media video and animation will become inestimably more complex and convincing. As anyone can testify who compares the elementary-school reports their computer-literate children compose with the reports from their own childhood, visual information has become increasingly available as a tool for communication, and every sign points toward that trend continuing and accelerating. Pictures, animations, and video will not supplant words, but they will become ever more prominent as supplement, as context. The interpretation of words alone will not suffice to account for this additional contextual matter. And interpretations in words alone will likewise seem increasingly paltry, when with so little extra effort one can illustrate one’s remarks with three-dimensional virtual models of the synagogues of second-century Palestine, or dynamic diagrams of Solomon’s social network, or animations of the dragon and the beast from Revelation—or something more like the holoscopic, pulsating colors of the Bible that Philip Dick describes.

As academic biblical interpretation moves more rapidly and comprehensively into domains other than the printed word, practitioners will need to learn how to evaluate interpretations on unfamiliar terms. Under present circumstances, the dominant critical question posed to (verbal) interpretations consists principally in whether they appropriately honor the historical context of the text’s origin; such questions well suit a discourse of interpretation that trades in propositions as its currency. When interpretations involve not only verbal truth-claims about interpretive propositions, but also shapes, colors, soundtracks, and motion, the matter of historical verisimilitude recedes among a host of other questions. The questions that most obviously fit cybermedia interpretations are more familiar from the worlds of film criticism, art criticism, and literary criticism (though this latter appears in this context in a mode less concerned with authorial intent and “original audiences” than with contemporary assessments of literary effect). These criteria feel awkward and subjective at present, but the effect of imprecision derives from inexperienced interpreters more than from the interpretive approaches. Scholars unfamiliar with construing biblical texts on any basis other than that of historical accuracy fumble and grope as they reach beyond the boundaries of their familiar practices. When academicians eventually become habituated to thinking aesthetically or ethically or politically about their interpretations, however, these modes of interpretation will seem no more subjective than interpretations based on varying assessments of historical probability.

One need not read tea leaves to suggest such a prospect. Brilliant scholars from eras past have deployed non-historical criteria freely in evaluating texts and interpretations. Critics who found a passage’s apparent literal meaning offensive applied ethical criteria to ground their conviction that the text must then mean something different from the literal sense. Medieval interpreters who saw edifying instruction in a biblical story made free to depict that scenario graphically without the constraints of historically-appropriate costume or topography. Handel’s Messiah confidently presses the case for a christological reading of Old Testament passages that bear no obvious messianic overtones when read in their historical social context. In such examples, biblically-erudite interpreters generate profound interpretations of texts without recourse to historical reasoning.

Interpreters from other cultural moments devised sound readings of biblical texts inasmuch as their social contexts provided cues that clarified the sorts of interpretation that might be encouraged, and the sorts of interpretation that should be stopped. Handel would have had no basis for making sense of claims that his Messiah illegitimately misconstrued the historical import of the Old Testament passages he cited. Philo sensitively recognized that his readers might be affronted by Lot’s drunken liaisons with his daughters, so he couched his exposition of that passage in terms of the relations of various intellectual faculties to one another. And at a moment when the cultural world of biblical interpretation trembled and warped under the stress of impending technological revolution, anonymous scholars composed the woodblock compositions that became known as the Pauper’s Bible, a mixture of graphic and verbal interpretations of the gospel, combining images drawn from the Old Testament, the Gospels, from pious legend and deuterocanonical narrative, to summarize a vast intertextual account of salvation history in forty woodcuts.

The woodcuts themselves represent what Edward Tufte calls a “confection,” a compilation of various sorts of images and information in a communicative ensemble whose whole vastly exceeds the sum of its parts. Editions of the Pauper’s Bible divide the printed (or hand-drawn) page into as many as eighteen small frames, each contributing a short text, the depiction of a character, or a scene from a biblical narrative (the number of frames in a given edition of the Biblia Pauperum may vary; one at hand shows twenty frames, another twelve). The eighteen frames do not simply stack up figures and texts in a jumble; instead, the illustrations and quotations constitute an interpretive context for the gospel passage that the central panel depicts. The illustrations in one frame echo visual motifs from the others, calling attention to connections between the illustrated passages that are absent from the literal sense of the quoted passages. They show the biblical figures in clothing and situations proper to the fifteenth-century milieu of the woodcuts’ composition, quietly making contemporary sense of the ancient writings. The careful arrangement of text and illustration—shaped by years of interpretive tradition and reproduction—encode and encourage a harmonized interpretation of the Bible’s message.

The Pauper’s Bible intimates one direction for post-print-media confections of biblical interpretation. Whereas modern biblical interpretation depends almost exclusively on the verbal medium of print, and its interpretive practices are haunted by the fantasy of a perfect translation, the Pauper’s Bibles mingle form and color with text (handwritten text, in some versions; woodcut text, in others). When we compare this premodern multimedia interpretive exercise to its modern successors, we are likely to recognize that the Pauper’s Bible lies closer to the frames, images, and text of a web page than do the lengthy expositions of contemporary academic scholarship. Add a few Quicktime animations, a streamed-audio background, and hyperlinks to other pages, and the fifteenth-century Pauper’s Bible already fits the present-day media world more comfortably than does the twentieth-century Journal of Biblical Literature.

The anonymous evangelical confections of the Pauper’s Bible bring us round, at last, to the second point I would press regarding the future of biblical interpretation as we modulate from a typographic interpretive culture to a cybermedia interpretive culture. The Pauper’s Bible testifies to the pivotal role that a disciplined imagination plays in biblical interpretation. For the past two centuries, interpreters’ imaginations have been policed by criteria native to the discipline of historical analysis; other approaches have been permitted to extend the range of biblical interpretation, to add a second interpretive dimension, only so long as they orient themselves toward the pole-star of historical soundness. Thus, literary criticism of the Bible frequently highlights the supposed editorial seams that enable historical interpreters to isolate distinct strands of a tradition; social-scientific interpreters foreground the social conventions of the Ancient Near Eastern and Hellenistic cultures from which the Testaments emerged. Historical reason determines the modern limits of legitimate interpretation.

Imaginations informed by cybermedia will not sit still for the ponderous police work of historical authentication. New media will oblige interpreters to extend the range of their interpretive and critical faculties—and the further our endeavors extend from the exclusively verbal interpretive practice of contemporary biblical scholarship, the less pertinent the fantasy of perfect translation and the imprimatur of historical verification will seem. New media will teach us new criteria. But as the Pauper’s Bible reminds us that the work of biblical interpretation has in past times communicated well in images, so the allegorical imagination that funded the Pauper’s Bible can provide clues the directions that critical interpretation may take in new media.

The contributors to ancient and medieval theology found in allegorical interpretation a device for expounding the Bible in the light of what they understood to be its plain sense, its more refined theological sense, its moral import, and its adumbration of things to come. Contrary to glib denunciations of this interpretive mode, their practice of the quadriga did not permit them to make Scripture say whatever they wanted, but brought to their consciousness the pertinent constraints on the range of permissible meanings. (The Reformation topos that allegorical interpretation makes a wax nose of Scripture, that can be twisted and reshaped in any way one likes, overlooks several salient characteristics of wax noses. Most important of these is that one cannot simply wrench a wax nose into twists and corners, flat stretches and pits, and still claim that it is a “wax nose”—any more than a potter can claim that her fresh-from-the-kiln ceramic vessel is a lump of clay. There are limits beyond which one cannot deform a wax nose without forsaking any claim to rhinosity—but within those limits, one may alter the shape of the wax nose as need dictates. That is the point of a wax nose.) The quadriga teaches four sets of criteria with which to evaluate representations of biblical texts; the fourfold approach to allegorical interpretation was not a license to permit imaginations to run wild, but a set of channels to guide interpretive imaginations. Those channels rely for their cogency not on intrinsic properties of words, but on an aptitude for drawing correlations, confections, that satisfy the imaginations of their readers. The allegorical criteria operate apart from the assumption that some property intrinsic to words provides the sole legitimating standard for critical interpretation, and they honor the inevitability that interpretations will go divergent directions without necessarily diverging from legitimacy.

The quadriga will not return in its premodern contours (though we could do worse). It may, however, stimulate thoughtful interpreters to authenticate their own electronic-media representations less compulsively on historical analysis, or on their approximations of a phantasmic perfect translation. These alternative criteria need not exclude the authority of historical studies; where interpreters want to make historical claims, they will always have to back those claims up with historical warrants. But as our capacity to imagine and interpret the Bible expands in ways that only a foolish forecaster would venture to specify, we stand only to benefit from observing the ways that our forebears dealt with assessing non-historical and non-verbal representations of the Bible. Some scholars will insist that the conventions of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries have established unsurpassable canons of hermeneutical validity, such that all representations from this day forward must pass the tests of historical and philological precision. If they are right, then all we need do to prepare ourselves for the oncoming wave of new media is to study ever harder the repertoire of historiographic and grammatical insights that they have handed down to us. They wisely commend to us the treasury that those insights offer. When change sweeps around and past us, however, we prepare best for an unforeseeable future by looking beyond the words with which our teachers enriched and bounded our understanding. We need to look beyond one or two dimensions of meaning and expression. We will need to acquaint ourselves with as full a range of interpretive possibilities as we can, and to seek a critical engagement with that range of representations which honors the richness of the interpretive imagination to which we are heirs, of which we are stewards on behalf of our neighbors and our successors.

Works Consulted

Abbott, Edwin A.

1884 Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions. New York: Dover Press, 1992.

Biblia Pauperum

1859 Introduction and bibliography by J. Ph. Berjeau. London: John Russell Smith.

Biblia Pauperum.

1867 Edited and introduced by Laib and Schwarz. Zurich: Verlag von Leo Wörl.

Biblia Pauperum.

1967 Introduction, notes, and subtitles by Elizabeth Soltész. Budapest: Corvina Press, 1967.

Biblia Pauperum.

1969 Introduced, transcribed, and translated by Karl Forstner. Munich: Verlag Anton Pustet.

Dick, Philip K.

1981 The Divine Invasion. New York: Pocket Books.

Eichenberg, Fritz

1992 Works of Mercy. Edited by Robert Ellsberg. Introduction by James Forest. Orbis: Maryknoll, NY.

Labriola, Albert C., and John W. Smeltz

1990 The Bible of the Poor [Biblia Pauperum]. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press.

Magritte, René

1929 “Les Mots et les Images.” In La Révolution surréaliste, 12 (December 15): 32-33. Reprinted in Écrits Complets, ed. André Blavier. (Paris: Flammarion, 1979), 60-61.

Sanders, Fred

1999a On Biblical Images: Dr. Doctrine’s Christian Comix, Vol. 1. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press.

1999b On the Word of God: Dr. Doctrine’s Christian Comix, Vol. 2. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press.

1999c On the Trinity: Dr. Doctrine’s Christian Comix, Vol. 3. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press.

1999d On the Christian Life: Dr. Doctrine’s Christian Comix, Vol. 4. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press.

Tufte, Edward R.

1997 Visual Explanations: Images and Quantities, Evidence and Narrative. Cheshire, Conn.: Graphics Press.

1990 Envisioning Information. Chesire, Conn.: Graphics Press.

1983 The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. Cheshire, Conn. Graphics Press.

Weinberger, David

2000 “Predictions.” All Things Considered, August 22.

What is the name of this book?

Melissa, the essay was originally published as “This Is Not a Bible,” in New Paradigms for Bible Study: The Bible in the Third Millennium, ed. Robert Fowler et al. (Philadelphia: Trinity Press International, 2004) 3-20.