I just don’t understand.

Very obviously, I don’t understand some things for technical reasons: I haven’t studied various topics in sufficient depth, I’m not the smartest character around, I hold to some premises that interfere with my giving other ideas full consideration. Nothing is comprehensible or unintelligible in itself; some apparently lucid ideas fail to fit functionally into the world in which they’re introduced, and some apparently bizarre ideas provide the most illuminating explanations for complex phenomena.

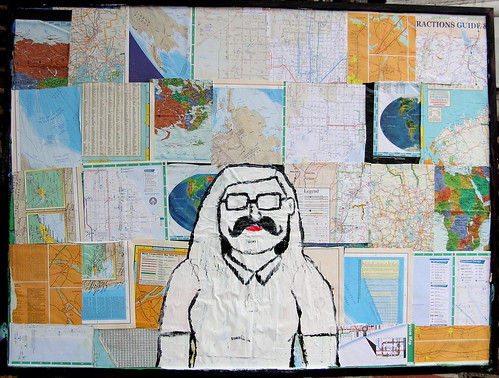

Now, after all that throat-clearing: I just don’t understand why people, smart people, still think that “the market” offers the most excellent way of assessing value and establishing trade patterns for goods and services. One can with a moment’s websurfing find examples of corporate executives who pull down salaries in the millions of dollars for presiding over the utter devastation of their firms’ assets; are we truly to believe that, because “the market” assesses the worth of their guidance at (let’s say) a couple million dollars, that they have actually contributed twenty thousand times as much to the general economy than does a day laborer who earns only ten thousand dollars? At least the day laborer’s work hasn’t harmed anyone; the postholes she drilled hold up actual fences, the burgers he flipped filled diners with empty calories. If the firm paying the two-million-dollar executive had actually just fired that character at the beginning of the fiscal year and relied on other employees to help make executive decisions, would the company have been that much worse off? Would our hypothetical day laborer have done a significantly worse job? Doesn’t the gruesome wreckage of these hypertrophic financial monsters suggest not that they’re “too big to fail,” but were in fact “too big to succeed” apart from transient, unmanageable fluctuations in the environment? If the financial services firm Engulf & Devour — or an entertainment corporation, or a widget, wodget, and aluminum storm door sales and manufacture company — encounters a stream of dollars, it can grow and thrive for a year or even a decade, but both plain reason and observed experience suggest that “the market” doesn’t dissuade investors, managers, executives, and politicians from chasing the easy money of cancerous economic growth in preference to the arduous nutrition and exercise of productivity, service, and modest rewards. It’s the same illogic that undergirds the music- and book-lottery industries (multi-millions for a handful of overpromoted superstars, versus a grudging pittance to tens of thousands of highly-skilled supporting acts): the lure of obscene wealth drowns out the actuality of widespread exploitation.

This is your “market”: a sociopathic, narcissistic Ponzi scheme raised up as the most reliable mechanism for distributing the resources that foster life, health, and happiness.

Stanley Fish’s recent article in the NYT touches on related topics, though in a way I take to be unhelpful. Fish proposes that because the humanities are not “useful” (according to market forces), they’re gradually being eroded by the market forces that shape academic enrollment, employment, and evaluation. As a quite-possibly-soon-to-be unemployed academic, I sympathize in part with Fish’s point. As a (theologically determined) humanist, though, I think that Fish manipulates his deployment of the term “usefulness,” and plays the contrarian game that has been his trademark since back when he argued against “Change” and in favor of ideas not having consequences. The schema involves constructing a very clear, precise definition of a concept, then showing that the concept (so understood) doesn’t display all of the characteristics conventionally associated with the concept (loosely understood). Outrage ensues!

I suppose Fish is probably correct that study in the humanities does not produce “a direct and designed relationship between its activities and measurable effects in the world” — but that implies not that the humanities are “useless,” but that they are useful in indirect, unmanageable ways, bringing about effects that do not easily lend themselves to quantitative analysis. The value of study in the humanities derives largely from its capacity to cultivate deliberative judgment about complex matters; that’s extremely useful, even if not in a way that fits Fish’s initial definition.

And to bring this round to the beginning topic, the sort of humanistic study that heightens our appreciation of, for example, David Copperfield, could quickly and accurately diagnose the dysfunction of market-driven binge-and-purge economics where the economists and fiscal policy pundits assured the world that all is well, that growth can continue unchecked, that this relocation of wealth upward will actually generate well-being all around. Even so tremendous a booster of the American marketplace as Horatio Alger promoted thrift, diligence, and critical evaluation — not misdirection, humbuggery, and evasion of responsibility for one’s avarice. Hey, the market made me do it.

I don’t understand that, and I tend to doubt that lectures on economics or anecdotes about righteous capitalists or tut-tutting condescension about what I don’t know about finance and management will illuminate me. But — my contract runs out in June, and from then on I’ll be available as CEO of your failing company. I pledge to drive your company into the ground on about the same schedule as the elite Wall Street wizard, but without the exorbitant salary and benefits. If I don’t make good on that pledge, you can dismiss me with a brass parachute.