[This page compiles in sequence the two-paragraph posts I’ve been writing one by one. As such, and as I’ve written the short posts over the course of months, I’m likely to have repeated myself, left an uneven transition, or some other mistake. Likewise, until I stop writing, it will probably end abruptly. It’s all part of the process.]

A great many hermeneutical conundrums fall away if one gives up the initial premise that words and language constitute the paradigmatic instance of meaning, expression, and communication. If one begins by recognising that words/language are the least typical instance of the domain constituted by modes of meaning, the way language works follows fairly simply.

This alternate premise will always be unpopular, because most people do not want to understand meaning so much as they want to control interpretation. The myth of subsistent meaning sustains that libido dominandi by positing a point of reference, a Sache, a kernel/pearl/nugget/“real meaning” to which the interpreter can lay claim. Neither “liberal” nor “conservative” scholars will yield on the (non-)existence of subsistent meaning, because all hope that they can deploy it to prove their case against the other.

(Comments)

Let’s start with waking up in the morning. My bedroom is lighter than it was several hours ago, perhaps even admitting a beam of light or two. I infer that it’s time to get out of bed, or at least to look at the clock. Where is the “meaning” in the ambient light? Or if it’s dark, grey, and cloudy, I expect rain; is there “meaning” in the clouds? In the lack-of-brightness?

We who are able to, we identify cues that experience has taught us to associate with situations — and to respond on the basis of that experience. Where (as in these examples) the cues to which we respond are not (typically) associated with intentional agency, we do not need to divine someone’s thoughts in order to ascribe some sort of “meaning” to sunshine, or clouds, or chilly winds, or long tracts of muddy field, or whatever. To this extent, we understand well enough the syntax of “meaning” in situations apart from [human] intentional agency. “When it is evening, you say, ‘It will be fair weather, for the sky is red.’ And in the morning, ‘It will be stormy today, for the sky is red and threatening.’”

(Comments)

I’d like to pause here for a moment to distinguish several usages of the verb “mean.” In the first, we say “I mean” in the sense of “I intend”; in a second, we say “That [word] means” in a lexical/semantic sense (“This word means ‘insubstantial’”); in a third, we say “That means” in the sense of an implication or entailment (“That means Heather is Robbie’s aunt!”). When we talk about “meaning,” it’s easy to slide from making claims about intentions to making claims about semantics, or to implications — and although I don’t suppose I’ve thought through enough possible examples to say that these should always be distinguishable, I certainly have seen cases in which an entailment has been used to warrant claims about an intrinsic semantic property. Likewise (to resume the example from last time), if we say “Red sky at night means good weather tomorrow,” the most fitting usage regards this as an inference from observation of weather patterns, not as a semantic property of red skies or as a celestial intention.

So we don’t need to succumb to the vapours if somebody (such as I) who opposes the notion of subsistent meaning uses the formulation “X means Y.” They might be using the phrase as an alternative to “X implies Y” (the option “X intends Y” won’t often come up as an intelligible possibility, I think). Or they may be using “X means Y” as a reasonable shorthand for “I can show numerous instances in which X is used synonymously, or ‘with the force of,’ Y.” The Greek word cheir (sorry, I haven’t bothered to change the DB_CHARSET setting in my wp-config.php file yet) means “hand.” Although I try to avoid this construction, Introductory Greek classes usually just want to know glosses, not semantic theory. Once you get beyond the very most simple glosses, though, the casual use of “means” tends to fund confusion about how languages and translation work. People can mean (intend) and circumstances can mean (imply) and words, glyphs, sigla, et cetera can “mean” (signify). In this last case, though, attributions of “meaning” always imply particular bounds, particular qualifications, and they never attain to simplicity or transcendence — we can’t appeal to “it just means X” or “it really means Y.”

(Comments)

Now, this is the pivotal dimension of my first premise: all interpretive activity involves inference as its key element. Whether I’m interpreting cloud formations, or the quality of light in my bedroom, or gestures, or spoken words (the interpretation of speech, especially in an unfamiliar language or accent, is a big clue here), or words on a page — all of these entail a practice of inferential reasoning. “It seems awfully bright — I may have slept late.” “Those clouds look heavy and dark — I should wear my macintosh.” “Her hand brushed mine — maybe she likes me!” “Ye cannae fling yer pieces oot a twenty story flat.” I notice; I ponder; I infer from what I perceive; I’ve attained an interpretation.

Contra approaches to interpretation that posit an intrinsic meaning which the interpreter endeavours to discover, the process of inference I’m describing here asks the question “Why does this look that way?” or “What accounts for these sounds in this sequence?” When an interpreter sets out to answer the question “What’s going on here?”, the range of appropriate responses may very sensibly include alternatives other than “the intrinsic meaning of this phenomenon — clouds, smell, light, pitch, tone, glyphs, touch, whatever — is X.” Where the phenomenon in question appears to involve an intentional agent, some interpreters will want to determine the likeliest intent that came to expression in the phenomenon. That’s not the only legitimate, only “normal,” only regulative, only ethical approach to take, however. Sometimes interpreters have a particular interest in considerations other than those that the intentional agent considered paramount. Sometimes the self-conscious intent in question differs from other dimensions of the expression (think of the small child, weeping, red-faced, loudly asserting “I’m not upset!”). Interpretation of phenomena comprises a great deal more than ascertaining the meanings of words and paraphrasing the combination of the words used.

(Comments)

“Inference” is a tricky category. We can think of plenty of instances for which we can specify precise criteria for successful inference, but these are swamped by the plenitude of situations in which successful inference from circumstances can be judged only on a rough-and-ready, close-enough sort of way. I can infer the time of day from the illumination filtering through my bedroom curtains, and that is ordinarily a satisfactory guide; but some mornings are exceptionally cloudy, or unexpectedly bright, and that pattern of inference really only works during the transition from night to day (it’s harder to distinguish 10:00 from 11:00 than 5:30 from 6:30 this time of year), some of us are better-attuned to morning light than are others, and of course some days the government instructs us to change our clocks by an hour. And even under the optimal circumstances, most of us can determine “It’s time to get up” but not “It’s exactly 6:47.” We do well enough (relative to particular expectations) almost all the time (but not absolutely always) by inferring time from bedroom-illumination; yet illumination-inference differs profoundly from consulting a radio-controlled digital timepiece.

Similarly, when Margaret and I need not to speak — when our infant children were sleeping, or when we’re observing an interval of silence, if we’re at a concert or in a gallery, or even if we’re playing Charades or Pictionary — we know one another well enough that we can often communicate effectively by gestures and facial expressions. Similarly, particular musical compositions generally evoke predictable sentiments among listeners. Colours apparently tend to cue particular physiological and behavioural responses. Scents, textures, noises, ambient temperatures, architectural and decorative spaces (awkward phrasing, can be improved), provide the basis for inferred responses. Some of these are highly predictable, some are more idiosyncratic, and the more aware we are of the degree to which a particular sensuous expression can be relied upon to evoke a particular response, the more successfully we negotiate the semiotic environment.

(Comment)

You have graciously borne with me in considering communication by wordless inference, in both non-intentional (“natural”) and intentional (“conscious animal life”) circumstances. I used inverted commas in my parenthetical characterisations because I’d like to allow for non-intentional inference in circumstances that aren’t simply “natural”, and because I want to be careful about what I say about intentional communication among some animals (without prejudging the circumstances for or against). Clearly animals interact in ways that seem to imply “communication” of some sort — and again, that’s all I’m after at this point.

I’m ready to add words to this picture, but please allow me to do so not all in a rush, but very slowly and carefully. Let’s go back to Margaret and me communicating; you’ve already allowed that we can get by, when we need to, without words (for topics that don’t require intense intricacy or precision). Once we begin to add words into the picture, our capacity to communicate effectively enters an entirely different domain of economy, precision, and effectiveness. We’re about to go buy some groceries; if we had to work out our shopping list, indeed even the premise of “going to the grocery store”, without words, we would take a very long time and might not arrive at a fully agreed agenda. With words, we can assent to the premise of a shopping trip, determine what we anticipate purchasing, and change our plans on the fly with minimal trouble. Yes, sometimes we misunderstand one another and find ourselves at cross purposes — but compared to the practice of communicating for such errands without using words, our verbal communication functions with fabulous ease and success.

(Comment)

You have graciously borne with me in considering communication by wordless inference, in both non-intentional (“natural”) and intentional (“conscious animal life”) circumstances. I used inverted commas in my parenthetical characterisations because I’d like to allow for non-intentional inference in circumstances that aren’t simply “natural”, and because I want to be careful about what I say about intentional communication among some animals (without prejudging the circumstances for or against). Clearly animals interact in ways that seem to imply “communication” of some sort — and again, that’s all I’m after at this point.

I’m ready to add words to this picture, but please allow me to do so not all in a rush, but very slowly and carefully. Let’s go back to Margaret and me communicating; you’ve already allowed that we can get by, when we need to, without words (for topics that don’t require intense intricacy or precision). Once we begin to add words into the picture, our capacity to communicate effectively enters an entirely different domain of economy, precision, and effectiveness. We’re about to go buy some groceries; if we had to work out our shopping list, indeed even the premise of “going to the grocery store”, without words, we would take a very long time and might not arrive at a fully agreed agenda. With words, we can assent to the premise of a shopping trip, determine what we anticipate purchasing, and change our plans on the fly with minimal trouble. Yes, sometimes we misunderstand one another and find ourselves at cross purposes — but compared to the practice of communicating for such errands without using words, our verbal communication functions with fabulous ease and success.

(Comment)

Adding words to our account of the communicative landscape does not fundamentally change what we’ve observed about inference and communication. Just as I make inferential estimates of what time in the morning it is (speaking of which, I need to find my sleep mask soon), or from my beloved wife’s mimed gestures when babies are sleeping, so I make inferential estimates of the most likely sense for the words she speaks or writes. There’s no “inner” or “real” meaning in the words; they’re a gesture, a verbal gesture, with the same status as a finger held to her lips, or a flat hand raised above her shoulder.

But that’s the second key element in the picture: when Margaret (or anyone, but we’re talking about Margaret now) speaks or writes words, they are words she has chosen based on her estimate (as speaker) of what I am most likely to infer from them. Again, there’s no intrinsic meaning at stake; she produces words calculated to elicit from me the results she wants. If she wants me to go to the grocery store to obtain food for dinner, she says, “Sweetheart, would you go to Tesco for a couple of things?” and it’s a pretty safe bet that I will in fact satisfy her desire. Were she to aim at the same effect by saying “Rapidly piddlepot strumming Hanover peace pudding mouse rumpling cuddly corridor cabinets?”, we may safely predict that the results would be different. Linguistic communication, on this account, is not sui generis nor paradigmatic for other modes of communication; it is continuous with other communicative modes, albeit in an extraordinarily precise, rule-governed way. It would be a dire mistake, however, to leap from “atypically precise” to “intrinsically precise” in order to amp up the degree of certainty that our inference can provide. We may be able often to recognise “time to wake up”, but that doesn’t entail our capacity really to ascertain that it’s 6:47.

(Comment)

To sum up from the past eight paragraphs, or so: Most of the problems in hermeneutics can be addressed most productively by regarding the problem as in interplay of expression and inference. A canvas by Monet entails one particular sort of expression; an installation by Tracey Emin is another sort of expression; Nigel Hess’s theme for the BBC television series “Campion” is another sort of expression; Margaret’s irresistible Oatmeal Lace Cookies are a different kind of expression; and a letter from St Paul is yet another sort of expression. St Paul expressed himself in words, but not only in words: although his facial demeanour, his posture, and vocal inflections are lost to us, we can be sure that we would apprehend his expression somewhat differently if we were on the spot. That doesn’t mean that our interpretations are insufficient in Paul’s physical absence, only we infer meaning differently when we draw on different pools of circumstantial information. When we have access to information that suggests that 1 Corinthians 14:34-35 are an interpolation into the text of Paul’s letter, some of us read the passage differently from the way we read it in the absence of that information.

Hence there is no intrinsic meaning. “Meaning” is something we infer, sometimes prospectively (before attempting a particular expression), sometimes retrospectively (drawing inferences from an expression from days past), sometimes in the moment (though of course that’s best considered as a blend of retrospect and anticipation — but all expression, I suppose, is extended in time). This sense of “meaning” — the zone where expression and inference, apprehension, uptake approach and perhaps converge — doesn’t require a subsistent quality to the words, paint, dough, marble, harmonies, or whatever. It partakes of the same faculties that make inferences about what wordless phenomena such as sunrise or smoke or the scent of bitter almonds imply. That’s the heart of my picture of hermeneutics: gesture and inference, expression and apprehension, offering and uptake.

(Comment)

For the purposes of my developing this argument, let’s take my expression-apprehension model of interpretation as read. On this account, now, we can explain a great many problems that the standard “subsistent meaning” account generates. For instance, the standard account gets into great headaches about “the difference between what it meant and what it means today” (Krister Stendahl); on the expression-apprehension model, there is no static “meant” or “means” to diverge. Under particular circumstances two millennia ago, people apprehended a particular expression in several identifiable and explicable ways; today, people apprehend the words of that expression (usually in translation, in this example) in several identifiable and explicable ways, and that’s just what we would expect. Is there an interesting, convincing vector of continuity among these apprehensions? My best answer to that sort of question involves the next paragraph.

A second persistent toothache for the standard account involves the question of how one gets from “meaning” to “application”. It’s all very well, we are told, to develop a technical argument that some biblical passage “means” X, but how do we apply that in the lifeworld? I answer that an argument about a text’s “meaning” that does not already (or imminently) correspond to a manner of living can be correct only in the most narrow of senses. In other words, “application” is not a problem to be solved in theory; ethos is itself a primary commentary on any purported textual application.

Êthos Anthrôpôi Daimôn, on Flickr

(Comment)

Summing up from last time: “meant” and “means” aren’t distinct from one another in the way that the standard account presupposes; and, there is no theoretical account to be adduced which will arbitrate how to apply a posited meaning. (This paragraph doesn’t count against me.)

Absent a subsistent “meaning” that provides a polestar for interpretive validity, we reckon the soundness of our interpretive activity by more proximate criteria. A tremendous proportion of interpretive legitimacy is not itself reasoned out, but “caught”, assimilated, from the interpreters whom one regards as authorities. Sometimes they hold authority by force: as in the academy, where students learn positively that “so and so is an admirable interpreter of whom our tutors speak highly, and we should endeavour to emulate his moves” or negatively that “Such and such never even appears on our reading lists; we can regard her work as utterly insignificant” or “Our tutor referred derisively to this book; we’d better not say anything good about it.” Learning interpreters strive to be like their positive models (“Be imitators of me, as I am of Raymond Brown” or “Tom Wright” or “Bart Ehrman”). Even among more advanced interpreters, a tacit sense of “what goes” in academic discourse affects the tenor of interpretive deliberation. We can make some of these criteria explicit, but others remain difficult to articulate (if we can recognise them as criteria at all, so deeply have they been assimilated).

Our interpretive activity does not simply observe the expression-and-apprehension interplay; it is itself an exercise in apprehension (of criteria, of tone, of acceptable conclusions, of audience) and expression (not only “This is my interpretation” but the representation of one’s deliberation as revolutionary or as compliant with extant discourses, as easily intelligible or as arcane, as authenticated by institutional authority or as self-justifying, and so on. The persona of the interpreter plays a role in the interpretation offered (“She explicitly alludes to Christian theological points of reference”, “He cites continental critics whose work I can’t read”, “He’s smartly dressed”, “She’s wearing shredded blue jeans”, “He slouches and mumbles”, “She looks us in the eye, speaks clearly and fluently and confidently”). All of these function willy-nilly, regardless of anyone’s intentions. The speaker/writer may intend to sound intelligent and confident, and a hearer/reader may think of him as pompous; a speaker/writer may intend to sound sensible and humble, and a hearer/reader think she’s not sure of herself and her case is weak. Even the most fair, even-handed, balanced interpreters are — cannot help being — affected by elements of a discourse that are not exhausted by an author’s intended meaning. Interpretive judgments comprise a great deal more than an inferred intent in words with subsistent meaning — and any account of hermeneutics that neglects, or suppresses, or circumvents, or denies the reality and power of these elements in the offering-uptake interaction misses some of the most important aspects of interpretation. And simply saying “Those other factors don’t count, they aren’t legitimate, we only accept the real meanings of words” doesn’t change the realities with which those who express and those who infer are daily dealing.

(Comment)

Observe the consequences of the few paragraphs we’ve walked through. Granted that there’s no subsistent “meaning”, and granted that verbal meaning is an atypical instance of the more general phenomenon of expression and inference, I submit that words in verbal communication function in the same way as gestures do in the frantically-mimed communication of someone who has just bit his tongue (for instance); there is no single exact right meaning to them. One may propose an indefinite number of meanings, depending on one’s interests. A psychoanalyst listens to your speech with specific interest to things that you are not saying, to things that you didn’t intend to say, on the basis of which she quite justly says “The meaning of these omissions and those unintended slips is….” Her assertion is not simply the assertion of a personal preference for viewing your slips and evasions in a particular way; you are both participants in a semiotic economy in which slips and evasions constitute an intelligible basis for interpretive inference.

“So can anything means anything? Are there no boundaries?” This question crops up all the time. Now, we know two things from the start: First, and this is important, we know full well that anybody can say “X means Y” no matter how daft we may think that assertion. At the same time, second, no assertion about meaning stands on its own; under most circumstances, such assertions carry the unstated subtext “In the semiotic economy of psychoanalysis…” or “Among all speakers of more-or-less standard English…” or “Assuming the speaker knew the word’s usual semantic range…”. Since those qualifying subtexts almost always remain tacit, though, it’s easy for people to mismatch assumed qualifications (“I thought we were talking about our relationship, and she thought we were talking about welfare policy”). Sometimes speakers deliberately operate with asymmetrical assumptions (psychotherapy again, for instance). And sometimes we deliberately interpret statements from one (presumed) semiotic economy in terms of another. But — and this is the key issue — no interpretive mandate can prospectively regulate the interpretations someone offers. (I’ve written about this before, in “Twisting To Destruction”; interpretive rules can function descriptively, but no interpretation was ever precluded because there was a rule against it.) Anything can mean anything to somebody, in some semiotic economy or another; the only boundaries come from our interest in participating in certain discourses, discourses where transgressive interpretive behaviour would be unwelcome.

(Comment)

Rules do not prevent bad interpretations. No one really supposes that they do, I hope; do we imagine a scene in which Dan Brown considers writing a megablockbuster novel, but then realises that his interpretive background for the novel and its claims that “All descriptions of artwork, architecture, documents, and secret rituals in this novel are accurate” were arrant poppycock, and so realises he simply can’t publish the novel. No one thinks there are sessions at the annual meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature at which a panelist jumps up and silences an interlocutor by saying “But you’ve broken this rule of interpretation.” Moreover, what would these “rules” be, and how did they come into effect? Before the interpretive rule, was misinterpretation not reckoned? Do interpretive rules govern everyone, or only those who assent to them (and if they don’t govern everyone, of just what use are they)?

The short answer to these question dodges their specifics, and gets straight to the heart of the matter: interpretive rules have [at least] two functions, one creditable, and one disreputable. The creditable use of interpretive rules sets them out as a guideline for the learner, or as an internal criterion for a more experienced interpreter. We don’t learn about interpretation all in one go, in a moment of blinding insight, and interpretive rules help us make our way from “whatever I feel like” toward “what makes sense to the people around me.” Such use of interpretive rules serves as a shorthand for “We resolve this sort of semantic or semiotic confusion according to that principle.” The disreputable reason for wanting interpretive rules is so that one can control interpretation. In the long run, this never works, but in the short run it can function to silence obstreperous dissenters. If it really worked, you would probably never have heard of Dan Brown.

(Comment)

Up to now, we’ve been moving from non-verbal, non-glyphic communicative modes and trying to see how verbal communication functions as a remarkable, powerful, precise extension of gestural, visual, aural (etc.) expression and apprehension. As gestures, sigla, tones, even patterns of smell and texture become familiar and eventually routinised with very particular associations and expectations, so verbal expression draws on intensely formalised associations and expectations to lead auditor-readers to reach particular interpretative inferences. But Chris Spinks’s recent blog reminds me that my expression-apprehension hermeneutic leads to an equally powerful insight in another direction.

Chris cites the example of the photo of a coathook which looks distinctly like a cockeyed pugilistic octopus once that interpretation has been suggested (original source seems to be lost to the wave of online replications; perhaps this is it, as noted by Reddit in 2010). Chris suspects rightly that this sort of phenomenon stands to shed some light on the hermeneutical puzzles that have long been bothering him, and it’s just the sort of “not from within our discipline” exploration from which these two-paragraph essays emerge. Once you see that “Dans un tableau, les mots sont de la même substance que les images”/“In a picture, the words are made of the same stuff as the images”,

a great many other things come clear as well (from the Magritte section in the Beautiful Theology blog). We communicate via all manner of gestures, sounds, images, scents, touches, and more; words are at an extreme of this repertoire, an outlying data point, but they’re not sui generis. And once you get accustomed to thinking of interpretive activity in terms of expression and apprehension, of gesture and inference, or offering and uptake, a great deal of what puzzles Chris looks much less mysterious.

(Comment)

On an “offering-uptake” model for hermeneutics, the hermeneutical problem becomes a problem of information design, an exercise in communicative strategy and tactics. Your communicative expression unfolds not solely in the words you choose (though those remain very important), but in the inflection with which you express those words, the gestures that accompany them, and so on. If you want to convey to your mother that you care for her, deeply and sincerely, and that you thank her for her maternal ministrations — then you probably oughtn’t to say, with a snarl, “Happy Mother’s Day, MOM.” (I do know at least one person who might well take that positively, though.)

That points to the variability of reception; your mother might be wounded by a snarky-sounding Mother’s Day greeting, whereas someone else’s mother might think that was just exactly the correct way to negotiate the complexities of expressing a threadbare sentiment in a hypercommercialised environment: “I’m supposed to say ‘Happy Mother’s Day,’ but if I just utter those words, they won’t effectively differentiate my greeting from the facile, cloying slogans on mass-marketed notecards; so I’ll pitch my voice to convey the sense that I’m only speaking out of a sense of obligation, and my hip mother with a lot of attitude will pick up the honest affection and respect that motivates me to speak.” The phrase “Happy Mother’s Day, Mom” can’t simply have intrinsic meaning; its force depends on how it is expressed, and on who is offering the expression, and to whom it is addressed, and so on. The words are only a small part of the interaction; the power of the gesture engages a whole congeries of modes and elements, and constructing a satisfactory Mother’s Day greeting requires one to consider information design (what to include, how to indicate emphasis or to cue particular types of response, how the anticipated audience is likely to apprehend the offered information, and so on), skill at putting that planned design into effect, good timing, and favourable contingent circumstances. Not. Just. Words.

(Comment)

If you’ve been following along more or less agreeably, you’ve assented to a number of very powerful points. You are on board with my characterisation of words as an extraordinary but highly atypical (hence, at risk of misleading) mode for expression and apprehension. You have allowed me the notion that any verbal mode of expression involves a great deal more than words alone, and it’s not that rare an event when words are among the less important elements of the semiotic economy. Of course, most importantly, you’re allowing me to proceed on the premise that meaning is not a quality inherent in any expressive gesture, but is a way of talking about the process of offering and uptake.

Now I’ll suggest something more contrary even than what I’ve been saying before: namely, that the distinction between “literal” and any alternative (“symbolic” or “figurative”. Or “spiritual”, for starters) confuses more than it clarifies, and should be abandoned. The principal uses of “literal” in polemical discourse all construct false differences, and many of the uses of “literal” in constructive discourse mystify the interaction they’re being used to advance. Although there are certainly innocuous ways to talk about the “literal” and its alternatives, the innocuous uses begin when the theoretician can say at the outset that this is just a heuristic distinction with no effectual purchase on words or reality. Where dominant discourses of meaning propose a distinction between “literal meaning” and “metaphorical meaning“, we should think instead in terms of more and less familiar (“conventional”, “probable”, “ordinary”) usage. Un-reifying the “literal” and “symbolic” clarifies quite a bit in our interpretive discourse, but that would take me beyond my two-paragraph-per-day limit.

(Comment)

Ages ago — the last time I blogged a two-paragraph hermeneutics post — I opened the case that the familiar distinction between literal and figurative (and its relatives “metaphorical” and especially “symbolic”) should be abandoned. Of course, the terms do very well for casual and heuristic purposes. I’m not in the least suggesting that we can’t say “No, I meant a literal brick wall” or “Donne’s use of metaphor sets him apart from his contemporaries.” The heuristic usefulness of the terms, however, does not warrant reifying the distinction nor extending it from a useful tool to a pair of ontological categories.

Symbols and metaphors work not because of mystical linguistic properties, but they work in the same way that literal language works. Where “literal” expressions rely on utterly familiar, unambiguously conventional usage, “metaphorical” language slides the usage from “quite predictable” further toward “unusual” (that could be as slight a difference as using a less common “literal” word or phrase) to “rather unconventional” (a word or phrase for which established patterns of usage haven’t worn a clear enough path to warrant calling the usage “literal” at all) to perplexing (“Is that a metaphor, or is she just talking nonsense?”). [I have two digressions to mark here, before I resume my second paragraph. First, yes, this is straight out of Nietzsche and Derrida, among others. As I said the other day, I’m not claiming to have invented this. Second, the relation between “metaphorical” and “nonsensical” warrants my exploring, too. Just not here.] In other words, metaphor isn’t an abuse of language, or a woo-woo special use of language: it’s a gamble on the part of the offerer (composer, artist, writer, speaker, whatever) that some portion of those who receive the expression will twig to the oblique association that the offerer envisions between the metaphorical phrase and what would be its ordinary, everyday, who-he-is-when-he’s-at-home “literal” usage. Sometimes those gambles don’t work out. Sometimes the oblique offering generates a rich field that includes unanticipated. But in the hands of a capable communicator, the choice of a less-than-obvious offering (be it linguistic or musical or a piquant combination of flavours) actually communicates very effectively indeed.

(Comment)

Rather than reifying “literal” and “metaphorical” as categories (or abandoning the notions altogether, per impossible), we understands the world better by treating expressions as more or less direct, perhaps, or obvious; or we can contrast “prosaic” with “poetic.” Such a gesture may appear superficial, a scrim of hermeneutical exactitude covering exactly the same discourses as before, but (to my mind) they serve helpfully to remind us that when we try to apply the “literal”/“metaphorical” dichotomy to other instances from the more general phenomenon of expression — let’s say “dance” and “baking” — it’s easy to see that they categories don’t work well. Some dance more closely simulates narratives and themes that it appears to depict, and other dance defies assimilation to such a schema. Some cooked foods involve the careful preparation of particular edible items without particular transformation (I’m partial to lightly stir-fried broccoli, for example) and other foods are prepared to resemble, or taste like, or suggest, other foods or inedible items or themes. That doesn’t make a medium rare steak more literal than a pizza whose ingredients are laid out in the configuration of a human face, or sushi made to resemble Ewoks (no, I’m not kidding).

We operate with a literal/metaphorical distinction in language because language offers a degree of conventional precision in expression that we find it convenient to deploy terms that point toward particular patterns of usage. Since no one’s going to mistake seaweed-wrapped rice for adorable short furry aliens from a Star Wars film, we don’t need to make that distinction. We struggle in graphic arts, working with the distinction between representational (or “photo-realistic”) and non-representational or abstract; likewise, even less successfully, in music. Instead of trying to force other expressive modes onto the Procrustean bed of linguistic precision (a precision that nonetheless falls short of what its partisans ask of it), we do better to recognise language as an atypical instance of expression, letting our expectations of language to begin from (and continue some of the imprecisions of) music, sculpture, cookery, and painting. Some verbal expressions are more evocative and indirect; some are more plain and obvious. And that’s OK, and it doesn’t require us to multiply entities.

(Comment)

Since the categories of “literal” and “metaphorical” don’t work in a straightforward way, we should be doubly suspicious about claims that that certain people do or do not read the Bible “literally.” Interpreters have long perceived one of the obvious hitches in this phenomenon — that certain elements of the Bible apparently ought not be taken literally (parables, for instance) — and have decreed that in some cases, the “literal” sense of the text is itself metaphorical. That provides a rickety, but viable, work-around, but it’s also a strong hint that the literal/metaphorical distinction entails significant conundrums. We need not restrict ouselves to abstract discussions of hermeneutical axioms, though; the plain, observable fact is that even interpreters who try to read the “literally,” for whom “literalness” marks their very public identity, do not in fact read the Bible literally. The principle of inerrancy trumps the principle of literalness, and in order to make every detail (including eschatological events that haven’t yet happened, as far as I know) warrantably correct, they construe apparently plain discourse in figurative, indirect, “symbolic” ways.*

I’m not so worried here about eschatological figures, though, as I am concerned about accusations of “literalism” (directed against conservative interpreters) and “only just a metaphor” (directed against “liberal” interpreters). When one group decries same-sex intercourse, their detractors accuse them of literalism; but those same detractors often enough proclaim that they favour feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, visiting prisoners, and so on. And similarly, when the apparent literal sense of a biblical text suggests something scandalous or unworthy about God or David or Jesus, some interpreters quickly find an indirect way of construing that passage — while others jump on it with glee, suggesting that the God whom Jews and Christians worship is a bloodythirsty, misogynistic sadist. Neither “literal” nor “metaphorical” effectively designates a consistent hermeneutical strategy. As readers, [almost] everyone needs to take some stuff “literally” and some stuff “figuratively” — but “More literal than those other guys” or “We only take the ideologically-acceptable stuff literally” don’t sell the product.

(Comment)

Finally, I hope, with regard to “literal”, as Bryan Bibb has been insisting, the literal-paraphrase equivalence spectrum as it applies to translation theory doesn’t hold water. Translation, as a fundamental interpretive act, partakes always of the metaphorical and literal both, and the translator’s taste, intuition, audience, fluency, imagination, and so on all affect questions of the success of a translation. However powerfully one may prefer one translation style or another, however good one’s reasons, there will not be an intrinsically “correct” or even “better” way of translating. The right way to translate is to learn the source language — but that renders translation otiose. Just as there is no “really means”, no “intrinsic meaning”, no objective, no ideologically innocent meaning, so there is no intrinsically good, bad, right, or wrong translation.

We can assess translations based on various criteria, but (again, as Bryan points out) these always interweave with political, ideological, theological, and other considerations. The best English translation for low-complexity readers may be Good News For Modern Man; the best translation for a conservative traditionalist independent church might be the King James Version (the best designation of which may be the KJV or the Authorised Version); a “progressive” congregation may choose to read from The Scholars Version. I might criticise each of those choices, but much of the force of my criticism would be blunted by the ideological differences between me and the audiences that adopt these different translations. In exasperation, as a shorthand, I may expostulate that the Scholars Version is just a bad translation, but the force of my rant remains that it’s a translation for which I’m not a fitting audience.

Of course, many times translators, audiences, and critics have in view a sort of maximal audience — an audience that wants very broadly sound semantic and syntactical judgments, fluent apprehension of both the source and target languages, and attentive appreciation of the source culture and its differences from the target culture. In those cases, arguments about good and bad have traction (though they’re still bounded by the explicit and latent assumptions of the author, translator, critic, and audience); but a great many of the remaining arguments boil down to arguments concerning taste. The “de gustibus” maxim does not cover this quite correctly, but it does point toward the difficulty and intractability of such arguments, arguments that we cannot expect to resolve on the basis of loud claims about the “real meaning,” the “literal sense,” or “objectivity.”

(Comment)

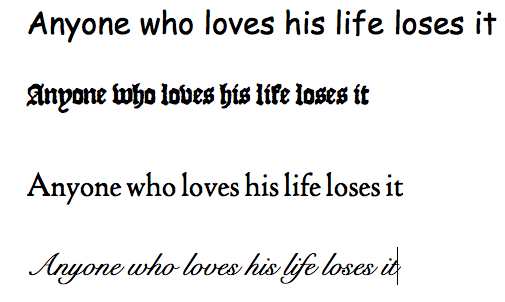

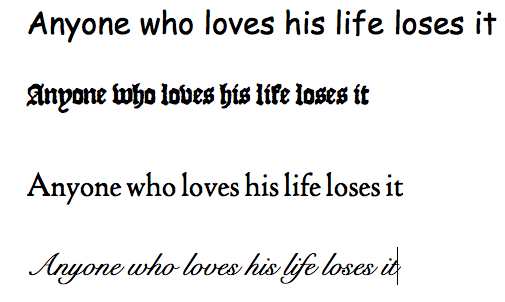

One last point that helps make my transition away from the literal/metaphorical distinction to the continuous interweaving of particular expressions in divers expressive modes: Even the most apparently nakedly verbal expressions entail inflections of appearance, tone, style that destabilise the question of whether they are “literal” (or even what “literal” means in such situations). To deploy an example I’ve used in other contexts, the same text represented differently must be allowed to mean differently:

Likewise, imagine the words “Yeah, sure, Mom!” spoken by an eager-to-please eight-year-old child and the same words spoken by a sullen teenager. A focus solely on the words of an expression can never attain the goal of a definitive account of what it means, no matter how determined and expert the researcher. Even if a researcher had access to the original verbal expression — and the idea of “original” in this context is itself intensely problematic — that researcher could never determine just what Snell Roundhand or Comic Sans “means,” what the aural notes of the spoken filial response “mean.”

When discussing and evaluating interpretations, the terminology of “correct” and “incorrect,” “really means” or “doesn’t mean” or “can’t mean” or “has to be understood as” or any of these arm-twisting expressions betrays a category mistake about the activity and goal of interpretation. We can always propose better or worse interpretations (and in specific circumstances these can casually but never rigorously be conveyed by “right” or “wrong”), and we can give reasons for our discernments — that’s it. The willed determination to squeeze “right” and “wrong” into the interpretation of verbal texts arises not out of an feature of textuality, but out of the interpreters’ desire to enforce their judgments upon others, to authorise binding inclusions and exclusions, to extract particular judgments from the to and fro of inevitable historical change and install them as idols of the technical cult.

(Comment)

On the premises I’ve been developing (and, I fear, repeating) here, we anticipate correctly that there will be no exact outcomes for interpretation — that when Rembrandt interprets the parable of the Good Samaritan, his painting will look different from the Chagall’s depiction in stained glass.

And not solely because they were working in different media — each of these interpreters wants us to focus on, to recognise different aspects of the story. Interpretive difference isn’t a problem, it’s an inevitable reflection of the profound differences that attend (and make up) our motivations, our audiences, our cultures, our capacities, our experiences, our media, and so on. The same principle applies to interpretive difference in linguistic interpretation; we stumble into the dead end of struggling for interpretive homogeneity from the extent to which we can align our linguistic interpretive interests into disciplines and practices that, when accorded effectual power in temporal affairs, upholds their own premises, axioms, methods, and so on as necessary, solely legitimate.

We can essay relative assessments of Rembrandt and Chagall just as easily as we can compare and evaluate Hans Conzelmann and Kavin Rowe — and just as easily as we can compare the interpretations of the Good Samaritan implicit in two government policy statements, or by the simple gestures of pedestrians who approach (and pass, or not) somebody curled up on the pavement. However insightful Rowe’s interpretive work on Luke’s Gospel, one oughtn’t imagine that he has more truly articulated its meaning than has a sympathetic passer-by who accompanies an injured man to a surgery, or an artist who produces a luminous window. If we bracket the impulse to treat interpretation as a zero-sum death match between muscular scholars struggling for domination, we can advance toward interpretive practices that both comport better with difference and afford ample space for articulating reasons for considering one better than another (by specific criteria).

(Comment)

If we don’t think about interpretation as decoding an encrypted meaning intrinsic to a particular expression, what do I propose that we think about interpretive processes (and especially the hard kind of interpretation, where we’re genuinely puzzled by an expression about which we care)? First, when we’re trying to puzzle out an interpretation we want to, try to, learn more about that expression. We accumulate some data about the expression and about features of the expression that seem salient to us based on our histories of successful interpretation. Very often we hark back to the question of what somebody wanted us to apprehend from an expression, asking “What did she mean?” and imitating Sherlock Holmes or the CSI team, searching for clues. At other times we put less emphasis on intention (for good enough reasons), but here I submit that our cardinal activity involves digging, researching, musing, parsing, seeking — wanting more information about the expression in the expectation that when we know more about it, we will perceive how best to interpret the expression in question.

Second — granted that we’ve turned up additional information of various sorts — we pursue a variety of activities that (ideally) help us to identify a satisfying paradigm for interpreting the expression in question. We analyse the expression, breaking it down into smaller bits; we correlate it, identifying it as a single example of a larger body of known data; we aggregate it, associating it as one data point in a greater field, which might be differentially weighted and assessed; and sometimes we explode it, project from it to fields and possibilities defined less by data already in hand than by hypotheticals we imagine on the basis of the expression. These are very rough and ready distinctions — I’ve already forgotten one or two, and I’ve changed the way I describe these even as I’m typing, so I’m sure I’m wrong about some of this and you can help me do it better — but they serve the heuristic purpose of underscoring that (for instance) looking a word up in a dictionary, or trying to remember why a saint might be depicted with a square halo, or other such activities differ from identifying an expression as a parable, or a devotional icon, or a delicious bowl of lentil soup; how saying that “All Cretans are liars” differs from “Very often, Cretans have lied to me and my family, although not always, so I will not instantly give credence (nor disbelieve) what this Cretan tells me.” And all these differ from “This soup discloses the future destiny of humankind,” or “I like to think that this is about times like when I just can’t get my necktie properly tied.” We dig up more interpretive materials, then by deliberation arrive at the most satisfactory ordering of “expression plus relevant additional considerations” we can find.

(Comment)

So if interpreting a text amounts to a sort of recipe in which a main ingredient is complemented, accompanied, enhanced by seasonings and cooking, one of the hoary tropes of interpretive discourse goes by the boards: namely, “the world of the text, the world behind the text, and the world in front of the text.” And I won’t miss it when it’s gone. It does appear to make sense at first, but if one takes it at all seriously, the trope’s utility rapidly dwindles and disappears. Same with “text as window, text as mirror” (and I always want to add “text as picture plane”). There’s no interpretive “behind” to a text, no “in front,” only an expression and the amplificatory adjuncts we use to complete a palatable interpretation. (No one eats their texts raw.)

What makes “the world behind the text” refer to a social, material, cultural gestalt (a “world”) different than “looking at a text in the contexts of social conventions, archaeological artefacts, and identifiable contemporary presuppositions”? Someone will say, “Don’t be such a grouch, it’s a heuristic pedagogical device!”, a mind-map for considering the relation of various interpretive regimes to the expression. Why then “behind”/“in front”? Why not “a pie of interpretive interests: some in the northwest of the compass, some in the south, some east-north-east”? My objection is not to using figures to facilitate understanding — but to reifying those models and using them sub rosa to enforce particular priorities and necessities. The “world behind the text” becomes a “real world” or a privileged originary setting; the “world in front of the text” becomes the reader’s world, distinct from and opposite to the pastness of the “behind.” The self-conscious readerly reader, though, is no more involved in discerning meaning than the self-abnegating historicist. Everyone in this game is looking at an expression, adding context until satisfied, and offering the result for social approbation. The best interpretations (by my lights, and probably by yours) involve reasoned culinary supplementation and preparation, not just “Aw, let’s just throw some spinach, clams, marmalade, and tarragon into the oven at 450° and see what it’s like after thirty-five minutes.” Culinary styles can be aggregated into schools and families, but medieval European cuisine isn’t intrinsically superior to Asian fusion. Expressions, additional information, interpretive approaches, bingo! And no “behind” or “in front.”

(Comment)

At this point — having catalogued the reasons for recuperating from the immanent-meaning hermeneutics of conventional interpretive discourses — we can better see the problems concerning “application” or about interpreting non-linguistic expression as problems that arise from taking an approach that works adequately for one particular interpretive practice and deploying it not only as a canonical method for other interpretive practices, but treating it as the authoritative approach. Thee’s nothing whatsoever wrong with looking for verbal equivalents, guided by authorial intention, when pursuing certain distinct ends. But that conventional approach misfires, stalls, falters and projects its own maladaptation onto practitioners and texts when brought to bear on non-linguistic expressions.

Linguistics scholars versed in relevance theory point to this as a breakdown of the “code metaphor”, the latent assumption that verbal (and often non-verbal expressions as well) expressions can be mapped one-to-one onto “interpretations,” in the way that a coded message can be decrypted by the methodical application of the correct process. (My paper “A Code in the Head” from the SBL a couple of years ago, which I cleverly posted over at Academia.edu instead of here, addresses this in more detail.) To repeat: rather than decrypting expressions according to “real meaning”, we venture attempts at apprehension, exchanging responses until we arrive at a mutually-agreeable state of satisfaction (or dissatisfaction). Relevance theory’s extremely convincing descriptive insights illuminate the aporias that arise from embedding the code metaphor into our interpretive assumptions. It goes awry when its practitioners go forward from there to treat relevance theory’s maxims as something close to a prescriptive regimen for interpretation (just as speech-act theory helpfully describes what usually goes on in communication, but goes catty-wumpus when it assumes prescriptive authority over interpretation). Sans code, however, we do our best to apprehend the rationale and import of an expression, and respond thereunto in the way that best expresses our understanding of the expression (utterance, gesture, composition, whatever) in view.

(Comment)

You may ask yourself — Why is this guy trying to hard, in so many ways, to disabuse us readers of the notion that there subsists a “meaning” as a property of a text, such that we correctly interpret that text by replicating as closely as possible the text’s subsistent meaning? This is not my beautiful text! This is not my beautiful meaning! You may ask yourself, but if you ask me I’ll reply, “Only when we recuperate from the misplaced premise of subsistent meaning can the innumerable benefits of taking an alternative approach come into clear focus. Only when we realise that we’ve been managing perfectly well without subsistent meaning can we see how much better we get along without that distraction.”

Once you accept the possibility that the extremely powerful consensus of language-users accounts sufficiently for success in linguistic communication (apart from any subsistent meaning) and, indeed, accounts much better for linguistic change and other phenomena, myriad implications crowd to mind. To take one example (one I used in my essay for Yale Div School’s Reflections), one can make the sound argument that the wisest interpretation of the Matthean Jesus’ parable of the sheep and the goats is not for an ageing white academic to write an article about the nature of parables, whether the sheep, goats, and recipients of charity are Gentiles, disciples, or any other group, but rather simply to go out and offer a meal to a hungry person. The practiced interpretation does not eclipse or invalidate the technical interpretation — and I’ll continue pursuing the more academic kind anyway, cos I just am that way — but discerning the meaning and applying the meaning aren’t necessarily separate processes. Moreover — and here we touch on a residual comfort of conventional subsistent-meaning hermeneutics — one can arrive at practiced interpretations clumsily, misguidedly, wrongly; but the same applies, as it turns out, to technical exegetical interpretation, and separating the latter out as the primary function of interpretation hasn’t demonstrably diminished the amount on interpretive “error” in churches and culture. It is more complicated than that — as is interpretation-as-practice — and neither exegetical diligence nor practical activism precludes the possibility of error. Nothing will protect you from error, or insure that you have the right interpretation that will authorise you to compel others to abide by your (that is, “the Bible’s”) command.

(Comment)